Judith Butler

"Torture, Sexual Politics, and the Ethics of Photography"

Judith Butler is Maxine Elliot Professor of Rhetoric and Comparative Literature at UC-Berkeley. She is the author of numerous books, including, most recently, Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence (2004) and Giving an Account of Oneself(2005) which addresses responsibility and ethics at the personal and political level.

演講錄音檔mp3下載位置:

http://deimos3.apple.com/WebObjects/Core.woa/Browse/itunes.stanford.edu.1292781236?i=109319874

2008/10/8

2008/9/30

Mal Waldron & Yosuke Yamashita (山下洋輔) / Piano Duo Live at Pit Inn

Mal Waldron & Yosuke Yamashita (山下洋輔)

Piano Duo Live at Pit Inn

1986

Sony CBS 32DH360

out-of-print

1. Duo Improvisation Part I

2. Duo Improvisation Part II

3.My Old Flame

hear it here.

2008/9/25

Abdullah Ibrahim (Dollar Brand) / Cape Town Fringe

1977

1977Bass - Paul Michaels

Drums - Monty Weber

Piano - Dollar Brand

Saxophone [Alto], Flute - Robbie Jansen

Saxophone [Tenor], Flute - Basil Coetzee

Drums - Monty Weber

Piano - Dollar Brand

Saxophone [Alto], Flute - Robbie Jansen

Saxophone [Tenor], Flute - Basil Coetzee

Tracklisting:

|

2008/7/27

Terumasa Hino Sextet / Fuji (藤)

2008/7/10

試論街頭攝影

銀座,東京 (2007)

試論街頭攝影

1. 「街頭攝影」的概念,在於攝影者走出斗室,用身體與感官接觸外在世界,並用輕便靈巧的攝影器材,將視覺感官所見事物記錄下來。

2. 在這種傳統論述中,「街頭」一詞成為外在世界的隱喻,充滿了隨機、即興、混亂,與不確定性,此一空間不若室內或攝影棚,能被拍攝者高度制約操控。

3. 人們手中的「相機」,在街頭攝影論述中被廣泛假定為,是個人感官的擴展及延伸,中介於攝影者的內在靈魂,以及外在環境的三度空間之間。但作為「中介 物」(mediator)的相機,絕非一毫無價值判斷之中立器材,它亦不只是如某些浪漫的攝影論述所言,僅是個人以視覺作為表現形式時的冥想工具 (meditative tool)。

4. 更多時候,人們帶著相機行走街頭,亦步亦趨、細心警覺地用光圈大小及快門速度的物理組合,藉著「採集」(人類學式的宣稱)或「獵取」(殖民式的姿 態)各類影像,將生活世界裡那種連續不斷、無法分割的三度空間/時間,武斷地凝結成斷裂零碎的二度空間,彷彿在這吉光片羽間,暗藏著某種無法言明的宇宙奧 秘或生命真理。

5. 這種街拍文化的極致,便是法國攝影家布列松(Henri Cartier-Bresson)的「決定性瞬間」概念。他認為”There is nothing in this world without a decisive moment”,而攝影者的職責及美學宗旨,就是試圖在雜亂喧鬧的世界裡,努力捕捉這個稍縱即逝的「瞬間」。在這種美學觀假設下,街拍文化極度講究構圖、 美學、色彩、線條等要素,如何能在單格影像裡達到形式上的醇熟。在這種美學觀的影響下,「真實」的本質彷彿就會在這靈光乍現的片刻,以「瞬間」的形式展現 出來。

6. 但是,任何對「真實」的展示,其實都不過是一種對「真實」的「再現」(representation)罷了,何以這瞬間的凍結,就能比其他片刻更具 有作為「真實」的正當性?畢竟單純、孤離的「片刻」本身,並不必然會讓吾等對影像「背後」那無法分割定格、總是彼此連貫的社會脈絡有更多理解。我們生活的 世界,總是一個互為因果、錯綜複雜的整體(totality),難以像剝洋蔥皮般,被幾個微不足道的快門聲所解剖切割。攝影在這個層次上,難以避免地是一 種化約。

Leica相機宣傳海報 (1929)

7. 布列松式的攝影者,其形象亦很類似德國哲學家本雅民(Walter Benjamin)的「漫遊者」(flâneur),有著他自己的節奏與步伐,並且「…...以為自己可以一眼看穿人潮中的路人的外表,洞察他的內心深處 的每一皺摺,將他定型歸類」。然而,這種試圖捕捉「決定性瞬間」的「漫遊者」,也很容易淪為自命閒適、浮光掠影,走馬看花的旁觀者,既不勤勉,也不深入, 更無觀點可言,最後淪為一個器材玩家。喜歡拿布列松傳奇當廣告的萊卡(Leica)相機,價格極度昂貴,便時常利用這種「理想攝影者」的形象,作為宣傳手 段。

8. 古典西方哲學對於人們如何認知外在世界,有著idealism與materialism的辯論,前者認為主體所認知到的外在客體世界並不堅實,其本 質其實奠基於個人內在意志心靈的主觀建構;後者則主張是外在客體的輪廓質地,制約並決定了主體的感官經驗。哲學家Henri Bergson為了克服這種主/客體分割的「二元論」困境,在《物質與記憶》一書中提出「形象」(image)之說。「形象」不同於單一、個別的「影 像」,它是「物質」的集合體,它大於idealism所認知到的representation,但小於realism所主張的thing,夾在心靈與物件 中途的「形象」,宛如主/客體之間的橋樑。在這種假說裡,「形象」已與「真實」有段差距,「攝影」更不過是對「形象」進行選擇性擷取的一種動作與「再 現」,在這種哲學觀下,「攝影」與「真實」間的距離也就無比巨大。

9. 街拍既又宣稱真實,卻又涉及選擇,面對這種困局,或許較為高明之道是去承認主體必然的介入,是去誠實接受這種弔詭矛盾,好另覓新徑。而非如某種古典 派的攝影美學,假設拍攝者總能像紳士般維持「數步之隔」的潔癖,環境再險惡也能保持冷靜酷性,狀似同情卻又不帶感情地,將景框內的構圖線條顧到盡善盡美。 的確,在這種古典街拍作品背後,彷彿總有一種喃喃自語的獨白,說著:「這是真實,我在場(並順勢捕捉),但某種意義上,也可以說,我不(用)在場(而這個 吉光片羽的瞬間依舊存在著)。」

《Self Portrait》 by Lee Friedlander (1970)

10. 在街拍與主體介入的議題上,美國攝影家Lee Friedlander的作品特別值得玩味。他在1970年發表的作品《Self Portrait》中,將自己在街頭拍照時的影子,大膽放入構圖之中,觀者看到他的身影宛如鬼魅或跟蹤狂,以陰影形式浮現在他所拍攝的客體之上。這系列作 品雖是街拍(一種對「外」的開展),卻也是攝影者自身肉體的殘骸展現(一種向「內」的考掘);名為「自拍像」,卻是沒有五官輪廓的「未完成式」,作 為”being”的主體,只能藉著朝向外在世界的不斷「運動」來”becoming”(一個不明確的)自身,而沒有終究完滿的一日(與他形成強烈對比的, 正好是擅長向「外」街拍的布列松,出了名地厭惡任何人試圖拍攝他肖像之舉)。藉此,Lee Friedlander試圖打破傳統街拍觀念裡,「自我」與「他者」之間那條宛如默契般、難以逾越的界線,在這種思維下,「自我與他者」(self and other)其實就是「自我即他者」(self is other)。而這種態度,也是1960年代後某些最秀異的街拍攝影家如William Klein、森山大道等人作品中的最大特色。

11. 街拍也是一種「運動」(movement),一種開展空間的姿態,一種”on the road”的態度,而Robert Frank在1958年發表的作品《The Americans》堪稱此種精神之極佳表現。《The Americans》是他花了2年時間在美國公路旅行,總共拍攝了兩萬八千張照片後,最後挑選出83張作品所濃縮而成,被公認為表現出1950年代末期美國社會的病理特徵與時代精神。

《Les Américains》 by Robert Frank (1958)

12. 《The Americans》被公認為街拍經典,但充滿自省精神的Robert Frank發現這種奠基於「瞬間」的攝影論述,完全不能滿足他對真實世界的巨大好奇。在英國ITV電視台拍攝的紀錄片裡, 他自承後來為了挑戰街拍美學的假設,有好一陣子將自己埋在公共巴士裡一整天,讓「機遇」的來決定自己能「被動地」在窗外看到何種社會景觀,再反射性地按下 快門。但這還不夠,1960年代後,因為街拍而名聲正旺前途似錦的他,有感於真實無法在瞬間中展現,拍照「頂多就是到個地方,看到個人,按下快門,然後走 開,完全沒有跟被拍攝者的交流可言」,失望至極的他,決定改拍紀錄片,好一陣子不再碰相機。

13. Robert Frank所談到的,攝影者與被攝者間的「交流」(communication)與否,是許多街拍論述的爭議焦點。有種街拍迷思主張,攝影者若能讓被攝者 不察覺到相機的存在,便能拍出最真誠的、最自然,最符合事實面貌的作品。這種講法最佳的實驗舞台,或許就是物理意義上不斷移動,但人們卻被迫暫時「不動」 的地鐵或巴士等通勤空間。很少有街拍者能抗拒在這種密閉卻又公開的矛盾空間裡,「偷拍」通勤男女的致命誘惑,早在1938到1941年間,美國攝影家 Walker Evans便嘗試將相機藏在大衣裡,希望能在「最低限度的人為因素介入下」,默默記錄紐約地鐵裡的眾生百態,但作為先行者,他早已警覺到其中可能涉及的倫 理問題,為了避免爭議,這一系列作品直到1966年,才以《Many Are Called》之名正式發表。

《Many Are Called》 by Walker Evans (1966)

《Subway Love》 by 荒木經惟 (2005)

14. 這種試圖抹除拍攝者「在場」證據的街拍實驗,在攝影史裡追隨者眾。日本攝影家荒木經惟的作品《Subway Love》便為一例。不過最有批判意味的,或許還是法國攝影家Luc Delahaye的1999年巴黎地鐵偷拍作品《L'Autre》。 Luc Delahaye的系列影像拍於1995到1997年間,當時法國已經訂定法律,宣稱每個人的影像只屬於自己,任何街頭攝影在未經他人同意下,皆有觸法之 虞。Luc Delahaye於是以類似Walker Evans的方式,在地鐵裡「竊取」這些肖像,最後成果是一連串冷漠的、空無的、被攝者與拍攝者間目光毫無交會的、巨大的空虛。不但拍攝者假裝自己與相機 「缺席」,被拍攝者也保持著當代都會中,陌生人目光刻意交避、偽裝對方隱形不存在的必要拘謹與相互默契。攝影者試圖「抹除」自己與相機「在場」的同時,被 攝者也成為一群刻意缺席的存在。這種自身在場與否及交流匱乏的危機,這種必要的冷漠與距離,這種溝通的短路與互為主體性的死亡,或許不單只屬於街頭攝影範 疇,更是當代社會的病徵之一。

《L'Autre》 by Luc Delahaye (1999)

15. 另一種關於街頭攝影的極端變體,則是將攝影者「在場」操控的程度提高到極致。這種街頭攝影,於是與室內的、攝影棚 式的美學實踐相差不遠,卻有另些值得玩味的空間。加拿大攝影家Jeff Wall是箇中好手,他的作品狀似即興、自然,許多照片乍看下更是最極端的「決定性瞬間」,但仔細考察,其實都是創作者事先設定好之畫面情節,仔細打燈布 置,請人歸位操演,再以笨重的大規格相機不斷嘗試,最後再選出單張成品所完成。他的作品雖然蘊含著各種街頭攝影的慣用詞彙(即興、真實、自然、瞬 間……),但其創作其實較接近傳統繪畫,甚或電影場景的思維。假如固守傳統街拍概念,他的作品或許顯得刻意做作,毫無意義,但持平而論,這不代表其作品的 批判力量,就必然比那種講求隨機感的街頭街拍薄弱。以他1982年的作品〈Mimic〉為例,便是對種族歧視的強烈控訴。

〈Mimic〉 by Jeff Wall (1982)

16. Jeff Wall作品裡的人們,就像電影裡的演員般,任由創作者擺佈。而這種高度操弄的,具有強烈「電影感」的街拍變體,在美國攝影家Philip-Lorca diCorcia的作品中,有另一種特殊的實踐方式。1989年他獲得NEA藝術創作補助,決定去好萊塢以流浪漢、性工作者、吸毒者等邊緣人為對象,拍攝 一系列街頭攝影作品。為了顛覆傳統街拍實踐中,拍攝者與被拍攝者缺乏「交流」的狀況,Philip-Lorca diCorcia改與被拍攝者進行「交易」,他將自己所獲得的創作補助獎金當作財源,以「開價」方式換取這些社會邊緣人的合作,讓他們走進攝影者所設定好 的場景劇碼裡充當主角,最後每幅單張作品,則以被攝者的姓名、年齡、出身地,以及「交易價碼」等「真實」資料作為標題。

〈Eddie Anderson; 21 Years Old; Houston, Texas; $20.〉 by Philip-Lorca diCorcia (1990~92)

17. 批評Philip-Lorca diCorcia者,會說他的作品嚴重剝削了這些被拍攝的邊緣族群,將人與人之間應然面的互為主體性,簡化為宛如性交易般不帶感情的物質交易。欣賞者則稱 其顛覆了真假之分,並從實然面挑戰了「拍攝者」與「被拍攝者」間那可疑又脆弱的關係。這是因為他的作品,某種程度上是「假」的,但也不完全假(那些場景, 確實不斷喚起確切存於人們心中的好萊塢文化迷思,而這些失敗的追夢人,真切地活在其中),但他和被拍攝者間的物質「交易」卻是真的;反倒是傳統街拍,內容 或許是真的,但拍攝者與被拍攝者間所謂的情感交流、理解、尊重,與溝通,卻很可能,且時常只是拍攝者片面的宣稱、矯情,與虛擬罷了。

18. 畢竟,誰擁有影像?「它」是拍攝者的獨斷權力,或是被拍攝者的自衛宣稱?兩者之間如何調和融洽,抑或衝撞辯證?更重要的是,街拍與「真實」間的關 係,究竟只是單純光學上的擷取,抑或有更深層值得爭辯的餘地?這些議題,過去不斷主導著關於街拍的辯論,亦會在未來繼續引導著街拍創作的實踐作為。

(原載於媒體改造學社論壇)

噪音的文化隱喻 (張傑)

轉載自http://corenna.blogbus.com/logs/2828551.html

噪音的文化隱喻

張傑

摘要:噪音在現代社會中的出現頻率越來越高,並因此形成一種有文化意味的現象。文章首先運用詞源考證法,考察噪音的最初能指,然後從作家或思想家們對噪音的態度和噪音音樂出發思考了噪音的兩種本原意義,進而從《白噪音》、《噪音:音樂的政治經濟學》等文本中發掘出噪音的多樣文化隱喻。文章最後表明對噪音所具文化隱喻的態度。

關鍵字:噪音;能指;所指;隱喻

噪音並非自工業革命後方才產生,從一般意義上理解,任何對他人的生活、學習或工作構成妨礙的聲音就是噪音。普通人解決的辦法無非是以口頭或動作表示抗議並努力消除之,不過值得注意的是,噪音在現代社會被描述為一種污染,可與工業、交通、建築等污染相提並論,而且被以法律和資料的形式嚴加規範。國家專門制定《環境雜訊污染防治法》,把超過規定的環境雜訊排放標準並干擾他人正常生活、工作和學習的現象,稱為環境雜訊污染。

如今,“噪音”一詞在生活中的出現頻率越來越高,足見其在現代社會中的深刻影響。本文意圖從追溯噪音的起源開始,對“噪音”的能指和所指作一粗淺的探索。

一

《說文解字》中,噪,擾也,從一開始,噪音就表示對別人的擾亂。此義古今中外概莫能外。不過,當時的“噪”寫作“譟”,可見更多的是指言語對別人的擾亂。後來,能指逐漸拓寬,諸如車聲,鼾聲,流水聲,動物的鳴叫,等等,只要對他人構成一定程度的干擾,就可以稱為噪音。人們可以比較自由地以睜眼或閉眼來表明自己對某事物的關注或排斥,正所謂一葉障目就能不見泰山,可忍受噪音對很多人來說卻是萬般無奈和被迫的,語音的穿透力和耳膜的脆弱性、暴露性使我們在喧囂吵鬧前非常被動。叔本華一本正經地說假如大自然打算叫人思考問題,她就不應當賜予他雙耳;或者,至少應當讓他長出一副嚴密的垂翼,就像蝙蝠所具有的那令人羡慕的雙翼一樣。他對人擁有耳朵耿耿於懷,“無論白天還是黑夜,他都必需始終豎張著雙耳以保持警惕,提醒自己注意追蹤者的接近。”[1]他本人深諳噪音之苦,認為噪音是世界上最不能容忍的東西,為此他不惜把一個製造噪音的女房客推下樓梯,結果為此承擔了三十年的贍養責任。他還將對噪音的厭惡寫成文章《論噪音》,編入他的論文集,在這篇奇文中他尤其談到鞭聲給他帶來的痛苦,“沒有比那可詛咒的鞭打更強烈的刺激了,你會感到那鞭打的疼痛簡直就在你的頭腦中,它對大腦的影響如同觸摸一棵含羞草那樣敏感,並在持續時間的長短上也是相同的。”在馬鞭的抽打聲中,叔本華覺得自己的思路越來越困難,“仿佛兩腿負重而試圖行走那樣困難”,因此他對噪音簡直是深惡痛絕,認為“在各種形式的紛擾中,最為要不得的要數噪音”[2]。

與叔本華極為相似的是卡夫卡,後者以小說的形式控訴了噪音的折磨。如他的《巨大的吵鬧聲》,“在此以前我就想到,現在我聽見金絲雀的叫聲我重又想起,我是否該把門打開一條縫,像蛇那樣爬進隔壁房間,蹲到地上,向我的妹妹們和她們的保姆請求安靜。”[3]比起叔本華來,卡夫卡對噪音的態度顯得軟弱無力。他認為唯有在安靜中創作才會得到身體和靈魂的雙重解放,他幻想最理想的寫作地點“在一個大的被隔離的地窖的最裏面。有人給我送飯,飯只需放在距我房間很遠的地窖最外層的門邊。我穿著睡衣,穿過一道道地窖拱頂去取飯的過程就是我唯一的散步。……那時我將會寫出些什麼來!我會從怎樣的深處將它們挖掘出來,毫不費勁!”[4]。儘管如此,他卻幾乎大半生時間都與父母同住,沒有主動避開家人製造的噪音。他對噪音表示的最大反抗就是對婚姻總是猶豫和反悔,雖然噪音並非他恐懼婚姻的唯一因素。

這種對噪音的深惡痛絕常人似乎難以接受,叔本華、卡夫卡等往往被認為有些病態和極端,人們甚至猜想這可能與他們的神經類型和身體狀況有關。但作家們並不買帳,餘光中憤然寫道“噪音害人于無形,有時甚於刀槍。噪音,是聽覺的污染,是耳朵吃進去的毒藥。”他認為,一切思索的或要放鬆休息的人都應該有寧靜的權利。因而,當社會不能給人提供安靜的生活空間時,一定是這個社會哪邊出了什麼問題。所以他提出“愈是進步的社會,愈是安靜。濫用擴音器逼人聽噪音的社會,不是落後,便是集權。”[5]由此,有無噪音上升為衡量社會進步與否的一個重要尺度,這就比叔本華和卡夫卡看得更具普泛的社會意義。後兩者只是把噪音視為個人寫作的干擾,叔本華更是從自我思考受阻的角度,指控噪音是那些精力體力過剩的人製造出來的,他甚至寫道:“我長期有這種看法,一個人能安靜地忍受噪音的程度同他的智力成反比,因此它可以看作衡量一個人的智力的很公正的尺度。……噪音對所有聰明人都是一種折磨。……用敲打、錘擊、摔四周的東西等形式來顯示過剩的生命力,都是我一生中天天必須經受的折磨。”[6]更甚之,他認為噪音“是一種純然放肆的行為”,“甚至可以說是體力勞動階層向腦力勞動階層的公然蔑視”[7],因此,叔本華以噪音劃分兩種勞動者的界限,並顯而易見地給出高下之分,其意圖在於彰顯思考和思考者的重要性,這與孟子“勞心者治人,勞力者治於人”的邏輯基本相同。叔本華還想當然地認為普通勞動者不會對噪音有什麼反應,因為他們不會思考,他們的大腦組織太粗糙。與卡夫卡隊寫作環境的幻想不同,他幻想的是假如生活於這個世界上的都是些真正有思想的人,那麼,各種噪音就不會如此肆無忌憚地擾亂世界的寧靜而無人制止了,這就有點像尼采的“超人”論了。卡夫卡雖強調寫作狀態,倒並沒有去刻意較量寫作與別種勞動的高下,也並沒有質疑勞動人群的生存理由,他更重視的是面對寫作個體生命的全然坦誠和投入。

當然,三者的共同點更明顯,都深刻地覺察到了噪音的危害,並呼喚對寫作者思考者的尊重,進而我們可以將之上升到呼籲對每一個人的尊重,這種尊重而且是與社會公民素質的提升成正比的。

其實,噪音不僅對知識份子,對普通人也類乎一種苦刑。現代工業和後工業的發展使噪音成為人體生命日難承受的污染,商場、超市、大街、建築、交通等無不是噪音的主要製造者。電影《青春無悔》中有這樣的情節:臥室外是無處不在的興建工程的噪音,主人公加農拿出一條細布繩緊緊綁在頭上以抗拒噪音帶來的頭痛。製作者將都市現代化給人們生活與文化造成的副作用以身體傷害——腦癌的形式呈現,寓意深遠,而主人公的父親告訴兒子忘記頭疼的辦法是更努力地工作,以噪音來對抗噪音,這顯然是十分反諷的。更為反諷的是,加農是負責拆舊房的——他既是受害者,又是都市的象徵和現代化的推動者。

噪音的高殺傷性的確不容忽視,因此能用作武器來對付他人。電視劇《西遊記》中有一集“觀燈金平府”,唐僧被三個犀牛精擄到青龍山,孫悟空單憑武功能打敗三個妖精,但是當眾多小妖圍成一圈沖著他狂叫,他卻敗出圈外,直到後來在耳中塞進棉花球方才打死小妖。還有一次是在女兒國遭遇琵琶精,後者一彈琵琶,孫悟空的腦袋就像被狠狠地蜇了一下,同樣因忍耐不得敗去。不過更可怕的是用噪音來逼供,將人關在鎖音效果極好的有高音喇叭的封閉房間裏,不斷播放噪音,四面的牆壁經過特殊處理還可以增大回音,這種懲罰不像毒打、夾手、坐老虎凳、灌辣椒水等直接傷及肉體,但囚犯卻往往能很快招供,忍耐不住這種特殊處理的噪音對神經的殘酷折磨。

還是在《你的耳朵特別名貴?》一文中,余光中先生說,人叫狗吠,到底還是以血肉之軀搖舌鼓肺製造出來的“原音”,無論怎麼吵人,總還有個極限,但是用機器來吵人,收音機、電視機、唱機、擴音器、洗衣機、微波爐、電腦,或是工廠開工,汽車發動,這卻是以逸待勞、以物役人的按鈕戰爭,而且似乎是永無休止沒有終結的——技術時代的人們必定要為享用技術付出代價:必須忍受馬路上高分貝的吵鬧,忍受狹隘的公共空間中的嘈雜,忍受電子產品雖微弱但執著的振動聲,而安靜,在今日都市卻日漸轉成上層人士和中產階層的特權,成為其社會地位和經濟能力的證明。魯迅《幸福的家庭》中的“他”,想通過寫小說來緩解窘迫的家境,他一邊努力虛構一個幸福家庭,一邊頻頻被妻子買菜和買劈柴的噪音拉回現實生活,最後不得不承認個性解放和生命自由的烏托邦破滅,不得不“俯首甘為稻粱謀”,其中噪音既諷刺性地提醒了小說中的人物,又昭顯了其窘迫的生存境況。

但人們也有喜愛噪音的時候,這表現在兩種情況中,一是自己並不需要安靜時自己發出噪音,此時是不管他人如何的,這也就是余光中先生深為之擔憂的公民素質和社會進步問題;另一種是全民狂歡,比如放鞭炮,人們對鞭炮聲大多並不表示反感,相反,多年嚴禁之後的限放政策讓很多人歡呼,不少居民不惜為之花費數千元,因此說是限放,實際上成了全放。更有專家來辯護“一刀切的禁放政策,使得傳統節日味道越來越淡,不僅令傳統節日日漸式微,阻礙了傳統文化的承繼和復興,而且使得辛勞了整整一年的公眾,其新春時節的快樂感和幸福感大打折扣”[8],爆竹越響似乎表示放爆竹者心情越暢快,財力越雄厚,但熱鬧顯然並不必然是繁榮穩定幸福的同義語。不過從人們的笑臉上可以看出,鞭炮製造的噪音在國人的意識裏一直代表著喜慶和熱情。

二

在《現代漢語詞典》中,噪音還有另外一種解釋,即音高和音強變化混亂、聽起來不諧和的聲音,由發音體不規則的振動而產生,與之相對的樂音自然就是有一定頻率,聽起來比較和諧悅耳的聲音,由發音體有規律的振動而產生。這是在嚴格的音樂意義上的比較。

20世紀以前的傳統音樂審美原則規定了樂音是組成音樂的基本語彙,但進入20世紀後,音樂創作發生了根本性的變化,現代主義對傳統幾乎作了全盤否定。1913年,義大利未來主義作曲家盧梭洛發表《噪音的藝術》,主張將噪音用作音樂作品的基本音響材料,以表現現代機械文明,並為此創作了由震動聲、軋軋聲、口哨聲等組成的噪音音樂作品。如同工業進入了繪畫一樣,噪音從此進入了音樂,比如“商店中金屬屏風的墜地聲,門砰然一聲關上的聲音,人群的喧嘩聲,各種各樣從車站、鐵路、鑄鐵廠、紡紗廠、印刷廠、發電廠與地鐵傳來的嘈雜聲,以及全新的現代戰爭的噪音”,甚至包括撕紙聲,咳嗽聲,腳步聲,等等。噪音音樂企圖告訴人們:在無限豐富的音響世界中,被作曲家用來建立音調體系的只是一小部分,生活中還有許許多多可供採用的音響材料,甚至一切聲音都可入樂。從某種意義上講,這倒頗合乎《禮記•樂記》中所說:“凡音之起,由人心生也,人心之動,物使之然也。感於物而動,故形於聲。聲相應,故生變,變成方,謂之音。比音而樂之,及幹戚羽旄,謂之樂。樂者,音之所由生也;其本在人心之感於物也。”[9]既然噪音也是現實事物造成的聲響,當然也能夠進入音樂的殿堂了。看似簡單的噪音加入,實際上,音樂的傳統定位就被深刻地改變了。早在兩千多年前柏拉圖就對音樂下結論說“和諧是永存的”,畢達格拉斯學派堅持音樂是對立因素的和諧的統一,把雜多導致統一,把不協調導致協調,甚至認為淨化靈魂的方法唯有音樂。老子也有言“音聲相和”,音者,樂音是也;聲者,雜訊是也。所謂“大音希聲”,大音者,不使雜訊過度喧囂之美音是也。從形式美的觀點看來,他們都認為音樂應該是優美的,就像春風微雨,嬌鶯嫩柳般溫和自然、舒緩靜態、輕盈流暢,使人得到平靜的愉悅。中國傳統音樂更是形成了“中和”的音樂審美原則:平和、恬淡,溫柔敦厚。如今,噪音介入甚至在有時佔據全章,自然使音樂顯得不那麼和諧了,由此引發了什麼是音樂美和如何鑒賞噪音音樂的爭論,最為激烈的怕是表現在對搖滾的爭執上。

上個世紀六七十年代,在美國搖滾遭到了猛烈攻擊,一些醫生從生理角度出發表達對搖滾的排斥,其理由是,搖滾樂高至110~119分貝的大音量嚴重超出聯邦政府制定的噪音標準,這種噪音比工業噪音還危險,還具破壞性,必將對人的內耳造成創傷,而且隨著揚聲器的輸出功率從60年代末的1000瓦發展到70年代中後期的近萬瓦,一些搖滾樂隊被指責為根本不是在演出,而是在製造電閃雷鳴。但是,隨後的研究發現,這些醫生的論斷並不科學,因為身處其中的搖滾樂手聽力並沒有明顯的破壞,因此又有醫生指出,噪音是否會對人的聽力造成損害取決於那種聲音對聽者構成的壓力大小,所以,如果聽者討厭搖滾,聽力可能受損,而如果是帶著興趣去欣賞,並視噪音為生活和工作中的一部分,聽力就不會受損[10]。

的確,對噪音音樂如何欣賞和評價是我們是否接受它的關鍵。旅美華人作曲家和電子媒體藝術家姚大鈞說:“人們剛接觸的時候會覺得一團混亂,沒有脈絡可循,仿佛隨便怎樣亂搞都可以搞出一套自圓其說的東西。其實,批評、解釋的法則與傳統音樂是一樣的。如果你要表達一種情緒,還是需要一定的技術,雖然是在用一種表面混亂的形式表達,但如果技巧不夠,一聽就能聽出來。”也就是說,搖滾等噪音音樂並非像一般人所說的那樣混亂不堪,傳統音樂的闡釋規則也可以運用。姚大鈞還寫過一篇《噪音聽法論》,序言裏說:“一般聽噪音音樂的方法,多半是讓自己完全臣服於這類作品中,以被虐狂式的心態讓高分貝的聲音海完全淹沒自己,並一定堅持到最後一秒鐘。”[11]

有很多像姚大鈞這樣的音樂人認為噪音在音樂中被重新賦予了生命,它激發著人的聽覺神經,將一份狂熱的感情推向極點,從目前搖滾在群眾中尤其是青少年中的普及程度來講,至少噪音音樂在一定範圍內已被認可,更有人將其上升為噪音美學,這一點還尚待專業人士確認。不容忽視的一點是,搖滾的噪音借助了現代技術(如大規模複製,高分貝播放手段,電吉他,電子合成,採樣拼貼,噪音實驗等)的東風。在流行音樂和搖滾的狂舞轟鳴中,古典的“天籟”(包括旋律、節奏與和聲)受到了衝擊,莊子所說的“動則失位,靜乃自得”也被擠到了舞臺上的最邊角。

三

從前兩部分來看,噪音無非有兩種能指,一指生活中刺耳的聲音,一指音樂中迥異於和聲的語言組成材料,但是,詞語的能指和所指往往是不等同的,“噪音”這個普通的詞語在當代也逐漸具備了新的文化隱喻。對隱喻德國哲學家凱西爾是這樣界定的:

“有意識地以彼思想內容的名稱指代此思想內容,只要彼思想內容在某個方面相似於此思想內容,或多少與之類似。”

他把隱喻視為“以一個觀念迂回地表述另一個觀念的方法”,簡單地說,隱喻就是以源域中的一個概念去解釋目標域中的一個概念,解釋是建立在二者的相似性或類似性基礎上的[12]。

美國作家唐•德里羅於1985年發表小說《白噪音》,該書之出名不僅在於它較為奇怪的標題,更在於標題本身揭示和象徵的蘊涵。作者自己是這樣解釋的,“關於小說標題:此間有一種可以產生白噪音的設備,能夠發出全頻率的嗡嗡聲,用以保護人不受諸如街頭吵嚷和飛機轟鳴等令人分心和討厭的聲音的干擾或傷害。這些聲音,如小說人物所說,是‘始終如一和白色的’。傑克和其他一些人物,將此現象與死亡經驗相聯繫。也許,這是萬物處於完美平衡的一種狀態。”這樣的解釋本身也難懂,作者接著又說,“白噪音也泛指一切聽不見的(或‘白色的’)噪音,以及日常生活中淹沒書中人物的其他各類聲音——無線電、電視、微波、超聲波器具等發出的噪音。”[13]這樣,我們就可以借用美國學者科納爾•邦卡所說,將現代科技產物的商品所發出的噪音均可稱為“消費文化的白噪音”,這是伴隨資本主義高度發展“自身釀制的苦果”。這一類白噪音,在小說中具體表現為電視和無線電廣播的各種節目,喋喋不休的廣告,超市和商城裏交易時人類的嗡嗡聲,甚至包括旅遊景點“美國照相之最的農舍”周圍照相機快門不停的喀擦聲。

如果白噪音的寓意僅止於此的話,那文章的這一部分完全可以併入第一部分,但是作者顯然要賦予白噪音更特別的隱喻。書中主人公傑克和妻子芭比特有這樣一段對話:

“沒有人看出來,昨夜、今晨,我們是何等的害怕——這是怎麼回事?它是否就是我們共同商定互相隱瞞的東西?或者,我們是否在不知情的情況下心懷同樣的秘密?戴著同樣的偽裝。”

“假如死亡只不過是聲音,那會怎麼樣?”

“電噪音。”

“你一直聽得見它。四周全是聲音。多麼可怕。”

“始終如一,白色的。”

“有時候它掠過我。”她說,“有時候它一點點地滲入我的頭腦。我試圖對它說話:‘現在不要,死神。”[14]

白噪音因此與人的死亡體驗緊密相關,掩藏著人對死亡的所有恐懼和想像。書中更精妙的一點還在其後,另一個小說人物默里把傑克的死亡恐懼看成是不自然的,正像他認為“閃電和雷鳴是不自然的”,他說傑克不知道怎樣自我壓抑,而在他看來,“我們自我壓抑、妥協和偽裝”方才是“我們如何倖存於宇宙之中的方式”,這種壓抑、妥協和偽裝就是“人類的自然語言”[15]。自然與非自然在小說中的所指已截然相反,所以白噪音除了作為物質社會的渣滓,最深切地表述了當代人對於死亡的恐懼,所有的經壓抑、妥協和偽裝而表現出來的白噪音還被認為表現出“人類交流死亡恐懼的努力和驅逐它的欲望”[16],如孩子長達七小時的無來由的哭泣,睡夢中發出的神秘聲音,修女們在根本不信任上帝和天堂的情況下日復一日的宗教說教,這些噪音在對抗死亡上達成一致。白噪音因此最終成為人類拒絕死亡的自然語言,真是莫大的反諷!

再回到我們第一部分談到的電影《青春無悔》,雖然噪音構成了對加農生命的威脅,但是如果沒有噪音,加農又能憑什麼居住在高樓大廈裏?噪音既是毀害生命的殺手,又是現代人生存不可或缺的依靠,甚或可以說,噪音在某種意義上隱喻著現代物質社會的蓬勃發展。

如果說白噪音還是從最普遍的社會生活角度,那麼法國人賈克•阿達利的《噪音:音樂的政治經濟學》就是從政治和經濟學意義對噪音作了耳目一新的闡釋,在此我們只談政治意義。他首先認為“不是色彩和形式,而是聲音和對它們的編排塑成了社會”,因此音樂與政治的關係更緊密,“與音樂同生的是權力以及與它相對的顛覆”,而與噪音同生的是混亂和與之相對的世界。在噪音裏我們可讀出生命的符碼、人際關係、喧囂、旋律、不和諧、和諧;當人以特殊工具塑成噪音,當噪音入侵人類的時間,當噪音變成聲音之時,它成為目的與權勢之源,也是夢想——音樂之源。它是美學漸進合理化的核心,也是殘留的非理性的庇護所;它是權力的工具和娛樂的形式[17]。噪音就是不和諧,就是異質和權力爭奪的化身。

上述闡述恰恰為“治世之音安以樂,其政和;亂世之音怨以怒,其政乖;亡國之音哀以思,其民困。聲音之道,與政通矣。”[18]作了現代注解,“怨”再上加“怒”顯然違背了“中和”的傳統音樂審美觀,因此可以說噪音產生於混亂和同樣混亂的世界中,或者說噪音就是亂世的徵兆。搖滾裹挾著沉重的音響設備,吼著電閃雷鳴般銳利至極的聲音,希望借此刺激青年使他們“從麻木不仁之中驚醒” [19],使他們意識到民主平等和平自由在當代現實理性社會中的匱乏,很多樂人包括中國的郝舫、崔健等人都一直是以這種觀點來欣賞和從事搖滾事業的,搖滾遭到以民主自詡的社會主流不遺餘力的攻擊在他們看來正是搖滾所寓政治意義的顯現。

在專制極權時代,一些往常被視為異類的事物會被藝術家們用來遙托寓旨,舉一個最簡單的例子,穆旦在1975年曾寫下一首短詩《蒼蠅》,“你永遠這麼好奇/生活著/快樂地飛翔/半饑半飽/活躍無比/東聞一聞/西看一看/也不管人們的厭膩/我們掩鼻的地方/對你有香甜的蜜/自居為平等的生命/你也來歌唱夏季/是一種幻覺/理想/把你吸引到這裏/飛進門/又爬進窗/來承受猛烈的拍擊”。蒼蠅這種製造噪音人皆厭惡的害蟲,在穆旦的筆下化為充滿理想色彩的追求平等者,最後被設下騙局使詐的人們所害。還有瘋狗(食指)、野獸(黃翔)、華南虎(牛漢),等等,它們發出的呼叫就成為抗爭那個淒冷壓抑時代的噪音。這個時候,沈默不再是金,高呼方顯英雄本色,所以1968年的“五月風暴”才永遠為世人感懷,沈默在彼時被視為無能和軟弱。

既然任何聲音就政治意義而言都是“權力的附屬物”和工具,面對這樣的噪音,極權主義者的回答必然是“查禁顛覆性的噪音是必需的,因為它代表對文化自主的要求、對差異與邊緣游離的支持”,阿達利指出,這種對維護音樂主調、主旋律的關切,對新的語言、符號或工具的不信任,對異於常態者的擯斥,存在於所有類似的政權中。所以,才會有了食指的瘋癲,黃翔的早逝,索爾仁尼琴的流浪,搖滾的被抑……

根據以上所述,我們可以借鑒福柯對權力的闡述來為噪音作一全面的界定。福柯認為,權力是“自下而上”的,大量的權力關係和權力形式存在於日常生活的橫斷面,存在於各種各樣的差異中,存在於任何差異性的兩點中,並“在各種不均等和流動的關係的相互作用中來實施”[20],那麼,既然噪音也是無處不在的,而且因一方的聲音高出或異于另一方而形成,我們同樣可以說,噪音存在於各種各樣的差異中,存在於任何差異性的兩點中,只要有差異,就會有噪音,就會產生對噪音的壓制和規訓。如此說來,任何超出常規具有異質色彩的事物均可構成噪音,尼采,凡高,《沉淪》,《呐喊》,《嚎叫》,貓王,《回答》,《男人的一半是女人》,《一無所有》,等等。

但是噪音絕對地有政治意義嗎?賈克•阿達利的論述和《禮記•樂記》分明向我們指出了這一點。可眾聲喧嘩究竟徵兆著民主的福音還是無序的混亂?還有噪音音樂的形式和它希望表達的內容統一嗎?越震耳欲聾就越能完好地宣洩對社會的不滿嗎?稽康在一千多年前就提出“聲無哀樂論”,反對從倫理觀、功能論出發去衡量音樂的美,所以搖滾的反叛從這一點來看又很值得質疑,倒是它的登峰造極的噪音有時的確讓人忍無可忍。德國美學家沃爾夫岡•韋爾施肯定地說“這些前衛派的實驗無以作為人類聽覺設計的指導方針,無以成為一種聽覺環境倫理學的指導方針。”[21]文章先後闡述了噪音的原始能指和新的文化隱喻,可以看到,

對噪音的厭惡,以及加諸噪音之上的那些隱喻,不過反映了我們的諸多不足:對安靜的強烈渴望,對現代化盲目崇拜造成的魯莽,對快節奏變化的焦慮和猶豫,對平庸的逃避,對自我和現實的不滿,還有我們在構建一個理想社會時不斷湧上的無力感。耳對噪音,灰色人群聽而不聞顯得滯鈍,他們更緊要的是去滿足基本生存需要,像叔本華所說的他們可能根本不需要作什麼抽象思考根本不擔心被打擾;中產階層則正力圖營構一個個愈發舒適的空間,向著心儀已久的上流社會直奔,自有隔離網使他們遠離一切噪音。在噪音中適應噪音,乃至忘卻噪音,築起“心齋”,恐怕是這個時代最明哲保身的生存策略。只是,人世的喧嘩與浮動,我們能完全躲得開嗎?即使躲得過,聰,察也,這樣的人還稱得上“聰”嗎?我還是願意這樣憧憬:一個平和理想的社會將很快出現,它將解決噪音以如此多樣和複雜的隱喻所反映出來的全部問題,每個人都將獲得思考和言語的權力與表達空間,噪音將被化解於無形。

The Cultural Metaphor of Noise

Abstract:There is a word which is getting a higher appearing frequency and one kind of cultural phenomenon thus comes into being. It is Noise. In this article, the author investigates noise’s original signal, then analyzes it’s two fundamental meanings from noise music and the writers’ or thinkers’ attitude to noise, and then unearths the multiple cultural metaphors of noise from White Noise, Noise:Political economics of Music ,etc. At the end of this article, the author expresses her attitude to these cultural metaphors of noise, expecting that a perfect society will appear and all the problems indicated by these metaphors of noise will get solved.

Key words:Noise;Signal;Signification;Metaphor

參考文獻:

[1]【德】叔本華. 論獨思..叔本華論說文集[M].範進等譯. 北京:商務印書館,1999. 355.

[2]【德】】叔本華. 論噪音.叔本華論說文集[M]. 範進等譯. 北京:商務印書館,1999. 492-493.

[3]【奧】卡夫卡. 卡夫卡短篇小說全集[M].葉廷芳主編. 北京:文化藝術出版社,2003. 211.

[4]【奧】卡夫卡. 致菲利斯情書.卡夫卡全集(第9卷)[M]. 葉廷芳主編. 呼和浩特:內蒙古人民出版社,1996. 213.

[5]餘光中. 你的耳朵特別名貴?[EB/OL].http://ww.chineseliterature.com.cn/xiandai/ygz-wj/021.htm,2006-07-01.

[6]叔本華:遲到的榮譽[EB/OL].http://www.grassy.org/Star/FPRec.asp?FPID=5683&RecID=3,2002-03-03.

[7]【德】叔本華. 論噪音. 叔本華論說文集[M]. 北京:商務印書館,1999. 494.

[8]湯萬君. 管理公共事務要勇於面對麻煩——從北京市煙花爆竹燃放“禁改限”說起[N]. 南方週末,2006-02-16(1).

[9]張文修. 禮記•樂記. 北京:燕山出版社,1995. 254.

[11]李宏宇. 北京聲納:用噪音做音樂[EB/OL].http://www.nanfangdaily.com.cn/zm/20031120/wh/dyyy/200311200876.asp,2003-11-20.

[12]【德】恩斯特•凱西爾. 語言與神話[M].於曉等譯. 北京:三聯書店,1988. 105.

[13]【美】唐•德里羅. 唐•德里羅致譯者信.白噪音[M] 南京:譯林出版社,2002. 1.

[14]【美】唐•德里羅. 白噪音[M]. 南京:譯林出版社,2002. 217.

[15]朱葉. 美國後現代社會的“死亡之書”(譯序).【美】唐•德里羅.白噪音[M]. 南京:譯林出版社,2002. 3.

[16]朱葉. 美國後現代社會的“死亡之書”(譯序).【美】唐•德里羅.白噪音[M]. 南京:譯林出版社,2002. 3.

[17]【法】賈克•阿達利. 噪音:音樂的政治經濟學[M].宋素鳳、翁桂堂譯. 上海:上海人民出版社,2000. 5.

[18]張文修. 禮記•樂記. 北京:燕山出版社,1995. 255.

[19]郝舫. 傷花怒放——搖滾的被縛與抗爭[M]. 南京:江蘇人民出版社,2003. 296.

[20]汪民安. 福柯的界限[M]. 北京:中國社會科學出版社,2002. 218.

[21] 【德】沃爾夫岡•韋爾施. 重構美學[M]. 上海:上海世紀出版集團,2006. 189.

2008/7/6

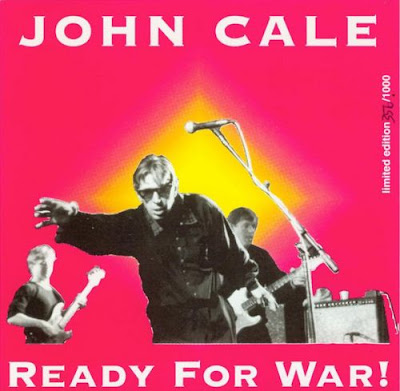

John Cale / Ready For War

Ready For War

Dischi-Dream Records DREAM 2,

Germany, 1993

1. She Never Took No For An Answer

2. Heartbreak Hotel

3. Mercenaries

4. Rosegarden Funeral of Sores

5. Jack The Ripper

6. Empty Bottles

7. Feast of Stephen

8. Sylvia Said

9. Nanna

10. Hallelujah (Leonared Cohen)

11. The Queen And Me / Queen Victoria (Leonared Cohen)

12. Last Day On Earth (extract)

13. Go West

14. Grandfather's House

15. First Evening

16. L'Heritage Du Dragon

17. Hunger

18. Villa Albani (instrumental)

1: from Sid & Nancy film soundtrack / 2: from June 1, 1974 / 3: 45 version / 4: 45 B-side / 5: unreleased test pressing / 6: Jennifer Warnes / 7: Mike Heron / 8: 45 B-side / 9: Patrizia Poli / 10: from I'm Your Fan / 11: from More Fans promo CDEP / 12: from Last Day On Earth / 13: Chris Spedding / 14: from One Word CDEP / 15, 17: Hector Zazou / 16: from Paris S'Eveille CDEP / 17: instrumental version.

倫敦大學鍊金術士學院優秀學長John Cale之珍稀曲bootleg合輯

2008/6/20

Aki Takahashi(高橋アキ)/ Hyper Beatles (1990)

日本前衛音樂/現代音樂鋼琴家Aki Takahashi(高橋アキ)重新翻玩/詮釋/解構Beatles眾多名曲之致敬專輯,其中包括John Cage所寫的The Beatles 1962-1970。

Out of print and very hard to find.

Aki Takahashi / Hyper Beatles

1990

Track Listings

1. Beatles Sweet: Here, There & Everywhere

2. Beatles Sweet: Blackbird

3. Beatles Sweet: Hide & Seek in Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown)

4. Beatles Sweet: Here Comes Lucy -- Here Comes the Sun

5. Yesterday

6. When I'm Sixty-Four

7. Something

8. Beatles 1962-1970

9. Michelle

10. And Love...-- And I Love Her

11. She Said, She Said

12. Fool on the Hill, Pt. 1

13. Fool on the Hill, Pt. 2

14. Goddess of Liberty -- You've Got to Hide Your Love Away

15. Short Fantasy on Give Peace a Chance

get it here

2008/5/13

[Reuters]Facial recognition technology to be used in Japanese cigarette vending machines

A new wrinkle in smoking enforcement...

Mon May 12, 2008 4:44pm EDT

TOKYO (Reuters) - Cigarette vending machines in Japan may soon start counting wrinkles, crow's feet and skin sags to see if the customer is old enough to smoke.

The legal age for smoking in Japan is 20 and as the country's 570,000 tobacco vending machines prepare for a July regulation requiring them to ensure buyers are not underage, a company has developed a system to identify age by studying facial features.

By having the customer look into a digital camera attached to the machine, Fujitaka Co's system will compare facial characteristics, such as wrinkles surrounding the eyes, bone structure and skin sags, to the facial data of over 100,000 people, Hajime Yamamoto, a company spokesman said.

"With face recognition, so long as you've got some change and you are an adult, you can buy cigarettes like before. The problem of minors borrowing (identification) cards to purchase cigarettes could be avoided as well," Yamamoto said.

Japan's finance ministry has already given permission to an age-identifying smart card called "taspo" and a system that can read the age from driving licenses.

It has yet to approve the facial identification method due to concerns about its accuracy.

Yamamoto said the system could correctly identify about 90 percent of the users, with the remaining 10 percent sent to a "grey zone" for "minors that look older, and baby-faced adults," where they would be asked to insert their driving license.

Underage smoking has been on a decline in Japan, but a health ministry survey in 2004 showed 13 percent of boys and 4 percent of girls in the third year of high school -- those aged 17 to 18 -- smoked every day.

(Reporting by Yoko Kubota; editing by Miral Fahmy)

Mon May 12, 2008 4:44pm EDT

TOKYO (Reuters) - Cigarette vending machines in Japan may soon start counting wrinkles, crow's feet and skin sags to see if the customer is old enough to smoke.

The legal age for smoking in Japan is 20 and as the country's 570,000 tobacco vending machines prepare for a July regulation requiring them to ensure buyers are not underage, a company has developed a system to identify age by studying facial features.

By having the customer look into a digital camera attached to the machine, Fujitaka Co's system will compare facial characteristics, such as wrinkles surrounding the eyes, bone structure and skin sags, to the facial data of over 100,000 people, Hajime Yamamoto, a company spokesman said.

"With face recognition, so long as you've got some change and you are an adult, you can buy cigarettes like before. The problem of minors borrowing (identification) cards to purchase cigarettes could be avoided as well," Yamamoto said.

Japan's finance ministry has already given permission to an age-identifying smart card called "taspo" and a system that can read the age from driving licenses.

It has yet to approve the facial identification method due to concerns about its accuracy.

Yamamoto said the system could correctly identify about 90 percent of the users, with the remaining 10 percent sent to a "grey zone" for "minors that look older, and baby-faced adults," where they would be asked to insert their driving license.

Underage smoking has been on a decline in Japan, but a health ministry survey in 2004 showed 13 percent of boys and 4 percent of girls in the third year of high school -- those aged 17 to 18 -- smoked every day.

(Reporting by Yoko Kubota; editing by Miral Fahmy)

2008/5/6

[Guardian]CCTV boom has failed to slash crime, say police

CCTV boom has failed to slash crime, say police

Owen Bowcott

The Guardian, Tuesday May 6 2008

Massive investment in CCTV cameras to prevent crime in the UK has failed to have a significant impact, despite billions of pounds spent on the new technology, a senior police officer piloting a new database has warned. Only 3% of street robberies in London were solved using CCTV images, despite the fact that Britain has more security cameras than any other country in Europe.

The warning comes from the head of the Visual Images, Identifications and Detections Office (Viido) at New Scotland Yard as the force launches a series of initiatives to try to boost conviction rates using CCTV evidence. They include:

· A new database of images which is expected to use technology developed by the sports advertising industry to track and identify offenders.

· Putting images of suspects in muggings, rape and robbery cases out on the internet from next month.

· Building a national CCTV database, incorporating pictures of convicted offenders as well as unidentified suspects. The plans for this have been drawn up, but are on hold while the technology required to carry out automated searches is refined.

Use of CCTV images for court evidence has so far been very poor, according to Detective Chief Inspector Mick Neville, the officer in charge of the Metropolitan police unit. "CCTV was originally seen as a preventative measure," Neville told the Security Document World Conference in London. "Billions of pounds has been spent on kit, but no thought has gone into how the police are going to use the images and how they will be used in court. It's been an utter fiasco: only 3% of crimes were solved by CCTV. There's no fear of CCTV. Why don't people fear it? [They think] the cameras are not working."

More training was needed for officers, he said. Often they do not want to find CCTV images "because it's hard work". Sometimes the police did not bother inquiring beyond local councils to find out whether CCTV cameras monitored a particular street incident.

"CCTV operators need feedback. If you call them back, they feel valued and are more helpful. We want to develop a career path for CCTV [police] inquirers."

The Viido unit is beginning to establish a London-wide database of images of suspects that are cross-referenced by written descriptions. Interest in the technology has been enhanced by recent police work, in which officers back-tracked through video tapes to pick out terrorist suspects. In districts where the Viido scheme is working, CCTV is now helping police in 15-20% of street robberies.

"We are [beginning] to collate images from across London," Neville said. "This has got to be balanced against any Big Brother concerns, with safeguards. The images are from thefts, robberies and more serious crimes. Possibly the [database] could be national in future."

The unit is now investigating whether it can use software - developed to track advertising during televised football games - to follow distinctive brand logos on the clothing of unidentified suspects. "Sometimes you are looking for a picture, for example, of someone with a red top and a green dragon on it," he explained. "That technology could be used to track logos." By back-tracking, officers have often found earlier pictures, for example, of suspects with their hoods down, in which they can be identified.

"We are also going to start putting out [pictures] on the internet, on the Met police website, asking 'who is this guy?'. If criminals see that CCTV works they are less likely to commit crimes."

Cheshire deputy chief constable Graham Gerrard, who chairs the CCTV working group of the Association of Chief Police Officers, told the Guardian, that it made no sense to have a national DNA and fingerprint database, but to have to approach 43 separate forces for images of suspects and offenders. A scheme called the Facial Identification National Database (Find), which began collecting offenders' images from their prison pictures and elsewhere, has been put on hold.

He said that there were discussions with biometric companies "on a regular basis" about developing the technology to search digitised databases and match suspects' images with known offenders. "Sometimes when they put their [equipment] in operational practice, it's not as wonderful as they said it would be, " he said. "I suspect [Find] has been put on hold until the technology matures. Before you can digitise every offender's image you have to make sure the lighting is right and it's a good picture. It's a major project. We are still some way from a national database. There are still ethical and technical issues to consider."

Asked about the development of a CCTV database, the office of the UK's information commissioner, Richard Thomas, said: "CCTV can play an important role in helping to prevent and detect crime. However we would expect adequate safeguards to be put in place to ensure the images are only used for crime detection purposes, stored securely and that access to images is restricted to authorised individuals. We would have concerns if CCTV images of individuals going about their daily lives were retained as part of the initiative."

The charity Victim's Voice, which supports relatives of those who have been murdered, said it supported more effective use of CCTV systems. "Our view is that anything that helps get criminals off the street and prevents crime is good," said Ed Usher, one of the organisation's trustees. "If handled properly it can be a superb preventative tool."

Owen Bowcott

The Guardian, Tuesday May 6 2008

Massive investment in CCTV cameras to prevent crime in the UK has failed to have a significant impact, despite billions of pounds spent on the new technology, a senior police officer piloting a new database has warned. Only 3% of street robberies in London were solved using CCTV images, despite the fact that Britain has more security cameras than any other country in Europe.

The warning comes from the head of the Visual Images, Identifications and Detections Office (Viido) at New Scotland Yard as the force launches a series of initiatives to try to boost conviction rates using CCTV evidence. They include:

· A new database of images which is expected to use technology developed by the sports advertising industry to track and identify offenders.

· Putting images of suspects in muggings, rape and robbery cases out on the internet from next month.

· Building a national CCTV database, incorporating pictures of convicted offenders as well as unidentified suspects. The plans for this have been drawn up, but are on hold while the technology required to carry out automated searches is refined.

Use of CCTV images for court evidence has so far been very poor, according to Detective Chief Inspector Mick Neville, the officer in charge of the Metropolitan police unit. "CCTV was originally seen as a preventative measure," Neville told the Security Document World Conference in London. "Billions of pounds has been spent on kit, but no thought has gone into how the police are going to use the images and how they will be used in court. It's been an utter fiasco: only 3% of crimes were solved by CCTV. There's no fear of CCTV. Why don't people fear it? [They think] the cameras are not working."

More training was needed for officers, he said. Often they do not want to find CCTV images "because it's hard work". Sometimes the police did not bother inquiring beyond local councils to find out whether CCTV cameras monitored a particular street incident.

"CCTV operators need feedback. If you call them back, they feel valued and are more helpful. We want to develop a career path for CCTV [police] inquirers."

The Viido unit is beginning to establish a London-wide database of images of suspects that are cross-referenced by written descriptions. Interest in the technology has been enhanced by recent police work, in which officers back-tracked through video tapes to pick out terrorist suspects. In districts where the Viido scheme is working, CCTV is now helping police in 15-20% of street robberies.

"We are [beginning] to collate images from across London," Neville said. "This has got to be balanced against any Big Brother concerns, with safeguards. The images are from thefts, robberies and more serious crimes. Possibly the [database] could be national in future."

The unit is now investigating whether it can use software - developed to track advertising during televised football games - to follow distinctive brand logos on the clothing of unidentified suspects. "Sometimes you are looking for a picture, for example, of someone with a red top and a green dragon on it," he explained. "That technology could be used to track logos." By back-tracking, officers have often found earlier pictures, for example, of suspects with their hoods down, in which they can be identified.

"We are also going to start putting out [pictures] on the internet, on the Met police website, asking 'who is this guy?'. If criminals see that CCTV works they are less likely to commit crimes."

Cheshire deputy chief constable Graham Gerrard, who chairs the CCTV working group of the Association of Chief Police Officers, told the Guardian, that it made no sense to have a national DNA and fingerprint database, but to have to approach 43 separate forces for images of suspects and offenders. A scheme called the Facial Identification National Database (Find), which began collecting offenders' images from their prison pictures and elsewhere, has been put on hold.

He said that there were discussions with biometric companies "on a regular basis" about developing the technology to search digitised databases and match suspects' images with known offenders. "Sometimes when they put their [equipment] in operational practice, it's not as wonderful as they said it would be, " he said. "I suspect [Find] has been put on hold until the technology matures. Before you can digitise every offender's image you have to make sure the lighting is right and it's a good picture. It's a major project. We are still some way from a national database. There are still ethical and technical issues to consider."

Asked about the development of a CCTV database, the office of the UK's information commissioner, Richard Thomas, said: "CCTV can play an important role in helping to prevent and detect crime. However we would expect adequate safeguards to be put in place to ensure the images are only used for crime detection purposes, stored securely and that access to images is restricted to authorised individuals. We would have concerns if CCTV images of individuals going about their daily lives were retained as part of the initiative."

The charity Victim's Voice, which supports relatives of those who have been murdered, said it supported more effective use of CCTV systems. "Our view is that anything that helps get criminals off the street and prevents crime is good," said Ed Usher, one of the organisation's trustees. "If handled properly it can be a superb preventative tool."

2008/4/26

Face scans for air passengers to begin in UK this summer

Face scans for air passengers to begin in UK this summer

Officials say automatic screening more accurate than checks by humans

Owen Bowcott

The Guardian,

Friday April 25 2008

Airline passengers are to be screened with facial recognition technology rather than checks by passport officers, in an attempt to improve security and ease congestion, the Guardian can reveal.

From summer, unmanned clearance gates will be phased in to scan passengers' faces and match the image to the record on the computer chip in their biometric passports.

Border security officials believe the machines can do a better job than humans of screening passports and preventing identity fraud. The pilot project will be open to UK and EU citizens holding new biometric passports.

But there is concern that passengers will react badly to being rejected by an automated gate. To ensure no one on a police watch list is incorrectly let through, the technology will err on the side of caution and is likely to generate a small number of "false negatives" - innocent passengers rejected because the machines cannot match their appearance to the records.

They may be redirected into conventional passport queues, or officers may be authorised to override automatic gates following additional checks.

Ministers are eager to set up trials in time for the summer holiday rush, but have yet to decide how many airports will take part. If successful, the technology will be extended to all UK airports.

The automated clearance gates introduce the new technology to the UK mass market for the first time and may transform the public's experience of airports.

Existing biometric, fast-track travel schemes - iris and miSense - operate at several UK airports, but are aimed at business travellers who enroll in advance.

The rejection rate in trials of iris recognition, by means of the unique images of each traveller's eye, is 3% to 5%, although some were passengers who were not enrolled but jumped into the queue.

The trials emerged at a conference in London this week of the international biometrics industry, top civil servants in border control, and police technology experts. Gary Murphy, head of operational design and development for the UK Border Agency, told one session: "We think a machine can do a better job [than manned passport inspections]. What will the public reaction be? Will they use it? We need to test and see how people react and how they deal with rejection. We hope to get the trial up and running by the summer.

Some conference participants feared passengers would only be fast-tracked to the next bottleneck in overcrowded airports. Automated gates are intended to help the government's progress to establishing a comprehensive advance passenger information (API) security system that will eventually enable flight details and identities of all passengers to be checked against a security watch list.

Phil Booth of the No2Id Campaign said: "Someone is extremely optimistic. The technology is just not there. The last time I spoke to anyone in the facial recognition field they said the best systems were only operating at about a 40% success rate in a real time situation. I am flabbergasted they consider doing this at a time when there are so many measures making it difficult for passengers."

Gus Hosein, a specialist at the London School of Economics in the interplay between technology and society, said: "It's a laughable technology. US police at the SuperBowl had to turn it off within three days because it was throwing up so many false positives. The computer couldn't even recognise gender. It's not that it could wrongly match someone as a terrorist, but that it won't match them with their image. A human can make assumptions, a computer can't."

Project Semaphore, the first stage in the government's e-borders programme, monitors 30m passenger movements a year through the UK. By December 2009, API will track 60% of all passengers and crew movements. The Home Office aim is that by December 2010 the system will be monitoring 95%. Total coverage is not expected to be achieved until 2014 after similar checks have been introduced for travel on "small yachts and private flights".

So far around 8m to 10m UK biometric passports, containing a computer chip holding the carrier's facial details, have been issued since they were introduced in 2006. The last non-biometric passports will cease to be valid after 2016.

Home Office minister Liam Byrne said: "Britain's border security is now among the toughest in the world and tougher checks do take time, but we don't want long waits. So the UK Border Agency will soon be testing new automatic gates for British and European Economic Area [EEA] citizens. We will test them this year and if they work put them at all key ports [and airports]."

The EEA includes all EU states as well as Norway, Switzerland and Iceland.

Officials say automatic screening more accurate than checks by humans

Owen Bowcott

The Guardian,

Friday April 25 2008

Airline passengers are to be screened with facial recognition technology rather than checks by passport officers, in an attempt to improve security and ease congestion, the Guardian can reveal.

From summer, unmanned clearance gates will be phased in to scan passengers' faces and match the image to the record on the computer chip in their biometric passports.

Border security officials believe the machines can do a better job than humans of screening passports and preventing identity fraud. The pilot project will be open to UK and EU citizens holding new biometric passports.

But there is concern that passengers will react badly to being rejected by an automated gate. To ensure no one on a police watch list is incorrectly let through, the technology will err on the side of caution and is likely to generate a small number of "false negatives" - innocent passengers rejected because the machines cannot match their appearance to the records.

They may be redirected into conventional passport queues, or officers may be authorised to override automatic gates following additional checks.

Ministers are eager to set up trials in time for the summer holiday rush, but have yet to decide how many airports will take part. If successful, the technology will be extended to all UK airports.

The automated clearance gates introduce the new technology to the UK mass market for the first time and may transform the public's experience of airports.

Existing biometric, fast-track travel schemes - iris and miSense - operate at several UK airports, but are aimed at business travellers who enroll in advance.

The rejection rate in trials of iris recognition, by means of the unique images of each traveller's eye, is 3% to 5%, although some were passengers who were not enrolled but jumped into the queue.

The trials emerged at a conference in London this week of the international biometrics industry, top civil servants in border control, and police technology experts. Gary Murphy, head of operational design and development for the UK Border Agency, told one session: "We think a machine can do a better job [than manned passport inspections]. What will the public reaction be? Will they use it? We need to test and see how people react and how they deal with rejection. We hope to get the trial up and running by the summer.

Some conference participants feared passengers would only be fast-tracked to the next bottleneck in overcrowded airports. Automated gates are intended to help the government's progress to establishing a comprehensive advance passenger information (API) security system that will eventually enable flight details and identities of all passengers to be checked against a security watch list.

Phil Booth of the No2Id Campaign said: "Someone is extremely optimistic. The technology is just not there. The last time I spoke to anyone in the facial recognition field they said the best systems were only operating at about a 40% success rate in a real time situation. I am flabbergasted they consider doing this at a time when there are so many measures making it difficult for passengers."

Gus Hosein, a specialist at the London School of Economics in the interplay between technology and society, said: "It's a laughable technology. US police at the SuperBowl had to turn it off within three days because it was throwing up so many false positives. The computer couldn't even recognise gender. It's not that it could wrongly match someone as a terrorist, but that it won't match them with their image. A human can make assumptions, a computer can't."

Project Semaphore, the first stage in the government's e-borders programme, monitors 30m passenger movements a year through the UK. By December 2009, API will track 60% of all passengers and crew movements. The Home Office aim is that by December 2010 the system will be monitoring 95%. Total coverage is not expected to be achieved until 2014 after similar checks have been introduced for travel on "small yachts and private flights".

So far around 8m to 10m UK biometric passports, containing a computer chip holding the carrier's facial details, have been issued since they were introduced in 2006. The last non-biometric passports will cease to be valid after 2016.

Home Office minister Liam Byrne said: "Britain's border security is now among the toughest in the world and tougher checks do take time, but we don't want long waits. So the UK Border Agency will soon be testing new automatic gates for British and European Economic Area [EEA] citizens. We will test them this year and if they work put them at all key ports [and airports]."

The EEA includes all EU states as well as Norway, Switzerland and Iceland.

2008/4/16

Thomas Ruff訪談 (Journal for Contemporary Art, 1993)

http://www.jca-online.com/ruff.html

Philip Pocock: Unlike the Neue Sachlichkeit of Sander or Renger-Patzsch, there is a clear crisis of belief in the objectivity of your medium in your work. True or false?

Thomas Ruff: It's both. It's true and false. They also used the camera as an instrument to take pictures. The difference between them and me is that they believed to have captured reality and I believe to have created a picture. We all lost bit by bit the belief in this so-called objective capturing of real reality.

Pocock: What do you mean by real reality?

Ruff: Photography has been used for all kinds of interests for the past 150 years. Most of the photos we come across today aren't really authentic anymore--they have the authenticity of a manipulated and prearranged reality. You have to know the conditions of a particular photograph in order to understand it properly because the camera just copes what is in front of it.

Pocock: Why did photography become so important in the art world?

Ruff: Maybe it's a question of generations. My generation, maybe the generation before, grew up with photography, television, magazines. The surrounding is different from a hundred years ago. Photography became the most influential medium in the Western world. So nowadays you don't have to paint to be an artist. You can use photography in a realistic, sachlich way. You can even do abstract photographs. It's become autonomous.

Pocock: There's little personality in your portraits, little use in the buildings, and a skepticism in photography' ability to communicate anything real in the Stars. Does this mean photography is empty in a traditional sense?

Ruff: It's empty in it sense of capturing real reality. But, for example, if I make a portrait, people say that there's little personality in it. They say that. But in a way there is because I know all of the people I photograph. Maybe the problem is that if in the same way I had photographed a famous person, it would be a different looking picture because we know another thing about this person.

Pocock: So they're anonymous . . .

Ruff: They're anonymous to you.

Pocock: You're dealing with the absoluteness of the medium, its picture perfectness. Would you agree with this?

Ruff: Photography pretends to show reality. With your technique you have to go as near to reality as possible in order to imitate reality. And when you come so close then you recognize that, at the same time, it is not.

Pocock: And what about your relation to the picture?

Ruff: Well, maybe I can say it's my curiosity that makes me do each one because I want to see them. And then I go on.

Pocock: When I look at one of your portraits, or buildings, it's almost as though I can see more than is actually there.

Ruff: But I think that happens because it's a picture. It's a frozen picture, nothing moves. If you stand in front of a building, maybe you turn your head because there's a noise, something moves, so there is not this concentration. But when a picture is on the wall, frozen, you get a totally different kind of concentration. And with the portraits you cannot stand in front of him or her and see them as you do in one of my photographs. That's impossible.

Pocock: It's well known that you studied photography with the Bechers. Was that the start?

Ruff: At that time I didn't know their work.

I took twenty of my most beautiful slides, landscapes of the Black Forest and holiday pictures. It was very strange because they accepted me. In the first year I had a brief talk with Bernd Becher about the slides. He said that they were more or less stupid because those photographs were not my own photographs but cliches, and they were an indication of the photographs I had seen in magazines. They were not my own.

Pocock: Have you turned that around on your teachers, like the portraits are clearly related to standard ID photos?

Ruff: Yes, sure. The portraits are definitely a construct based on identification photographs.

Pocock: And the newspaper photographs are not your own?

Ruff: I couldn't do all that by myself. It was also important for me that they have already been printed, that they had been so-called important enough to be worth printing, even if they are only illustrations for a text. So the photograph itself doesn't tell you anything; it's the text that does. And if I cut off the text, what happens then?

Pocock: What quality do you look for in an news photograph?

Ruff: You know, all the newspaper photographs are standard, archetypal, like politicians shaking hands, or a rocket blasting off, a landscape somewhere. I can't tell you more than that. I just see it and I know it's the right photograph. Not that it' good but it makes a point for my idea.

Pocock: Some quick questions: What do you think of Irving Penn, Richard Avedon?

Ruff: I like them.

Pocock: Walker Evans, Eugène Atget?

Ruff: In my first years at the academy they were my most important influence. Perhaps Stephen Shore and William Eggleston were of similar importance to me there as the older documentary photographers but within color. And I still like looking at them.

Pocock: How does the American school of the seventies large-format photography differ form the Düsseldorf school?

Ruff: I think it's just a different landscape. America looks different from Europe.

Pocock: Why color in the portraits and not much color anywhere else?

Ruff: Color is close to reality. The eye sees in color. Black and white is too abstract for me.

Pocock: Why stars? Do they mean something extra special to you?

Ruff: When I was eighteen I had to decide whether to become an astronomer or a photographer. I also wanted to move the so-called künstlerische Fotografie boundary. Do you know Flusser?

Pocock: No.

Ruff: He defines isolated categories for photography that sometimes cross over. For example, if medical photography is used in a journalistic way, or with the Stars, a scientific archive isn't used for scientific research but for my idea of what stars look like. It's also a homage to Karl Bloßfeldt. In the twenties he took photographs of plants to explain to his students architectural archetypes. So he was a researcher but the way he represented his intention with the help of photography made him an artist. I like these crossovers.

Pocock: What about the buildings you photograph?

Ruff: I choose the buildings like the people I photograph. I know them from driving around and sometimes it makes click. Then I have to go back and see if it is really something, if it's possible to photograph it. I don't look for high architecture but that average style you find in any suburb of any Western city. It's color, shape, line. It's more geometric.

Pocock: How do you see repetition in your work?

Ruff: I wouldn't say repetition, but I would say I work in series. Not to prove to myself that I was right but I'm not satisfied with one picture but maybe with ten or fifteen or forty.

Pocock: I feel a certain anxiety when I see the portraits hung in a series. I'm reminded of that game as a kid: What is wrong with this picture?

Ruff: It's not "What's wrong?" but "It's a big puzzle." With one photograph there isn't enough information. Even I couldn't explain to an extraterrestrial all of mankind with my forty portraits of my friends. You cannot explain the whole world in one photograph. Photography pretends. You can see everything that's in front of the camera, but there's always something beside it.

Pocock: Have you ever done portrait commissions?

Ruff: Not so much, but when I did portraits, people came and asked me. At that time everything was ready for doing portraits so I said, okay, sit in front of the camera.

Pocock: Is it something you tried to avoid?

Ruff: In my series of portraits they are all young, Some of those commissions I would never use for exhibitions.

Pocock: When you show so many portraits all at once, are you trying to convince us of something?

Ruff: Convince?

Pocock: To persuade us of something about these people?

Ruff: Maybe I have to say it differently. I've been asked a lot why my portraits never smile. Why are they so serious? They look so sad and like that. And I've been thinking about that. Maybe it has something to do with my generation. Like I use all-over lights, no shadows. We grew up in the seventies. The reality was that there was no candlelight. If you go through a place, through the car park, it's always fluorescent, so no shadows, just the all-over light. And in the seventies in Germany we had a so-called Terrorismushysterie: the secret service surveyed people who were against nuclear power; the government created or invented a so-called Berufsverbot. This meant left-wing teachers were dismissed, so sometimes it was better not to tell what you were thinking. All over we have those video cameras, in the supermarkets, the car park. In big places everywhere you've got those cameras. If you stand in front of a customs officer, you try to make a face like the one in your passport. So why should my portraits be communicative at a time when you could be prosecuted for your sympathies.

Pocock: This notion of surveillance seems to link nicely with the Night work. How far are you with this new Surveillance series?

Ruff: I started thinking about it at the beginning of last year. I had the idea of combining the surveillance aspect of the portraits with the darkness of the Stars.

Pocock: Are they all that green and black?

Ruff: Yes, I use a light-amplifying lens that is normally installed in tanks or military jets to see at night. It's another prosthetic use of the medium. If you use a microscope or a telescope you always see something you can't see with the naked eye.

Pocock: Why is it green?

Ruff: It's the authentic color from the phosphorescent screen and if it's green, it's green.

Pocock: Do you feel that one day you'll give up photography for electronic processes?

Ruff: I'm happy to work again with my own photographs after being in the studio since 1989 with the Stars and Newspaper photographs. Now I go out at night.

Pocock: They look like pictures of privacy. Are you investigating the idea of privacy?

Ruff: The first pictures I made were of backyards. It was January and really cold so I visited friends and took pictures from their rear windows.

Pocock: Is there a little bit of the voyeur in every photographer?

Ruff: These have been done with a device that detectives are starting to use, so they can work on stealing privacy.

Pocock: To solve crimes?

Ruff: Yes, this picture looks as though it could be a scene of a crime.

Pocock: The crime of photography. Is photography itself a crime?

Ruff: It can be.

Philip Pocock: Unlike the Neue Sachlichkeit of Sander or Renger-Patzsch, there is a clear crisis of belief in the objectivity of your medium in your work. True or false?

Thomas Ruff: It's both. It's true and false. They also used the camera as an instrument to take pictures. The difference between them and me is that they believed to have captured reality and I believe to have created a picture. We all lost bit by bit the belief in this so-called objective capturing of real reality.

Pocock: What do you mean by real reality?

Ruff: Photography has been used for all kinds of interests for the past 150 years. Most of the photos we come across today aren't really authentic anymore--they have the authenticity of a manipulated and prearranged reality. You have to know the conditions of a particular photograph in order to understand it properly because the camera just copes what is in front of it.

Pocock: Why did photography become so important in the art world?

Ruff: Maybe it's a question of generations. My generation, maybe the generation before, grew up with photography, television, magazines. The surrounding is different from a hundred years ago. Photography became the most influential medium in the Western world. So nowadays you don't have to paint to be an artist. You can use photography in a realistic, sachlich way. You can even do abstract photographs. It's become autonomous.

Pocock: There's little personality in your portraits, little use in the buildings, and a skepticism in photography' ability to communicate anything real in the Stars. Does this mean photography is empty in a traditional sense?

Ruff: It's empty in it sense of capturing real reality. But, for example, if I make a portrait, people say that there's little personality in it. They say that. But in a way there is because I know all of the people I photograph. Maybe the problem is that if in the same way I had photographed a famous person, it would be a different looking picture because we know another thing about this person.

Pocock: So they're anonymous . . .

Ruff: They're anonymous to you.

Pocock: You're dealing with the absoluteness of the medium, its picture perfectness. Would you agree with this?

Ruff: Photography pretends to show reality. With your technique you have to go as near to reality as possible in order to imitate reality. And when you come so close then you recognize that, at the same time, it is not.

Pocock: And what about your relation to the picture?

Ruff: Well, maybe I can say it's my curiosity that makes me do each one because I want to see them. And then I go on.

Pocock: When I look at one of your portraits, or buildings, it's almost as though I can see more than is actually there.

Ruff: But I think that happens because it's a picture. It's a frozen picture, nothing moves. If you stand in front of a building, maybe you turn your head because there's a noise, something moves, so there is not this concentration. But when a picture is on the wall, frozen, you get a totally different kind of concentration. And with the portraits you cannot stand in front of him or her and see them as you do in one of my photographs. That's impossible.

Pocock: It's well known that you studied photography with the Bechers. Was that the start?

Ruff: At that time I didn't know their work.

I took twenty of my most beautiful slides, landscapes of the Black Forest and holiday pictures. It was very strange because they accepted me. In the first year I had a brief talk with Bernd Becher about the slides. He said that they were more or less stupid because those photographs were not my own photographs but cliches, and they were an indication of the photographs I had seen in magazines. They were not my own.

Pocock: Have you turned that around on your teachers, like the portraits are clearly related to standard ID photos?

Ruff: Yes, sure. The portraits are definitely a construct based on identification photographs.

Pocock: And the newspaper photographs are not your own?

Ruff: I couldn't do all that by myself. It was also important for me that they have already been printed, that they had been so-called important enough to be worth printing, even if they are only illustrations for a text. So the photograph itself doesn't tell you anything; it's the text that does. And if I cut off the text, what happens then?

Pocock: What quality do you look for in an news photograph?

Ruff: You know, all the newspaper photographs are standard, archetypal, like politicians shaking hands, or a rocket blasting off, a landscape somewhere. I can't tell you more than that. I just see it and I know it's the right photograph. Not that it' good but it makes a point for my idea.

Pocock: Some quick questions: What do you think of Irving Penn, Richard Avedon?

Ruff: I like them.

Pocock: Walker Evans, Eugène Atget?

Ruff: In my first years at the academy they were my most important influence. Perhaps Stephen Shore and William Eggleston were of similar importance to me there as the older documentary photographers but within color. And I still like looking at them.

Pocock: How does the American school of the seventies large-format photography differ form the Düsseldorf school?

Ruff: I think it's just a different landscape. America looks different from Europe.

Pocock: Why color in the portraits and not much color anywhere else?

Ruff: Color is close to reality. The eye sees in color. Black and white is too abstract for me.

Pocock: Why stars? Do they mean something extra special to you?

Ruff: When I was eighteen I had to decide whether to become an astronomer or a photographer. I also wanted to move the so-called künstlerische Fotografie boundary. Do you know Flusser?

Pocock: No.

Ruff: He defines isolated categories for photography that sometimes cross over. For example, if medical photography is used in a journalistic way, or with the Stars, a scientific archive isn't used for scientific research but for my idea of what stars look like. It's also a homage to Karl Bloßfeldt. In the twenties he took photographs of plants to explain to his students architectural archetypes. So he was a researcher but the way he represented his intention with the help of photography made him an artist. I like these crossovers.

Pocock: What about the buildings you photograph?

Ruff: I choose the buildings like the people I photograph. I know them from driving around and sometimes it makes click. Then I have to go back and see if it is really something, if it's possible to photograph it. I don't look for high architecture but that average style you find in any suburb of any Western city. It's color, shape, line. It's more geometric.

Pocock: How do you see repetition in your work?

Ruff: I wouldn't say repetition, but I would say I work in series. Not to prove to myself that I was right but I'm not satisfied with one picture but maybe with ten or fifteen or forty.

Pocock: I feel a certain anxiety when I see the portraits hung in a series. I'm reminded of that game as a kid: What is wrong with this picture?

Ruff: It's not "What's wrong?" but "It's a big puzzle." With one photograph there isn't enough information. Even I couldn't explain to an extraterrestrial all of mankind with my forty portraits of my friends. You cannot explain the whole world in one photograph. Photography pretends. You can see everything that's in front of the camera, but there's always something beside it.

Pocock: Have you ever done portrait commissions?

Ruff: Not so much, but when I did portraits, people came and asked me. At that time everything was ready for doing portraits so I said, okay, sit in front of the camera.

Pocock: Is it something you tried to avoid?

Ruff: In my series of portraits they are all young, Some of those commissions I would never use for exhibitions.

Pocock: When you show so many portraits all at once, are you trying to convince us of something?

Ruff: Convince?

Pocock: To persuade us of something about these people?

Ruff: Maybe I have to say it differently. I've been asked a lot why my portraits never smile. Why are they so serious? They look so sad and like that. And I've been thinking about that. Maybe it has something to do with my generation. Like I use all-over lights, no shadows. We grew up in the seventies. The reality was that there was no candlelight. If you go through a place, through the car park, it's always fluorescent, so no shadows, just the all-over light. And in the seventies in Germany we had a so-called Terrorismushysterie: the secret service surveyed people who were against nuclear power; the government created or invented a so-called Berufsverbot. This meant left-wing teachers were dismissed, so sometimes it was better not to tell what you were thinking. All over we have those video cameras, in the supermarkets, the car park. In big places everywhere you've got those cameras. If you stand in front of a customs officer, you try to make a face like the one in your passport. So why should my portraits be communicative at a time when you could be prosecuted for your sympathies.

Pocock: This notion of surveillance seems to link nicely with the Night work. How far are you with this new Surveillance series?

Ruff: I started thinking about it at the beginning of last year. I had the idea of combining the surveillance aspect of the portraits with the darkness of the Stars.

Pocock: Are they all that green and black?

Ruff: Yes, I use a light-amplifying lens that is normally installed in tanks or military jets to see at night. It's another prosthetic use of the medium. If you use a microscope or a telescope you always see something you can't see with the naked eye.

Pocock: Why is it green?

Ruff: It's the authentic color from the phosphorescent screen and if it's green, it's green.

Pocock: Do you feel that one day you'll give up photography for electronic processes?

Ruff: I'm happy to work again with my own photographs after being in the studio since 1989 with the Stars and Newspaper photographs. Now I go out at night.

Pocock: They look like pictures of privacy. Are you investigating the idea of privacy?

Ruff: The first pictures I made were of backyards. It was January and really cold so I visited friends and took pictures from their rear windows.

Pocock: Is there a little bit of the voyeur in every photographer?

Ruff: These have been done with a device that detectives are starting to use, so they can work on stealing privacy.

Pocock: To solve crimes?

Ruff: Yes, this picture looks as though it could be a scene of a crime.

Pocock: The crime of photography. Is photography itself a crime?

Ruff: It can be.

Thomas Ruff訪談

http://www.brooklynrail.org/2005/06/art/thomas-ruff

Thomas Ruff with Vicki Goldberg

by Vicki Goldberg

The German photographer Thomas Ruff achieved international recognition in the 1980s alongside Thomas Struth and Andreas Gursky, all students of Bernd and Hilla Becher. Of these three influential photographers, Ruff is the most experimental in theme and technique. He made his name with monumental, straight-on, emotionally uninflected portraits and went on to photograph—or appropriate and enlarge photographs or Internet images of—architecture, interiors, landscapes, nudes, stars, machines, and newspaper photos; he has also made night-vision photographs, superimposed negatives, and created montages, stereographs, and computer-altered images, including abstractions derived from Japanese manga.

In March, David Zwirner in New York showed Ruff’s recent altered photographs based on JPEG photographs from the Internet. This work made Ruff’s concern with questions of perception immediately visible: the pictures were nearly indecipherable from a great distance, resolved into recognizable images of landscapes and catastrophes at a middle distance, and dissolved into a mass of pixels up close. This interview was conducted in person in New York and later extended by e-mail.

Thomas Ruff: When I started at the Kunstakademie in 1977, I was an amateur. I took photographs like the ones you find in amateur magazines. I wanted to travel around the world taking beautiful photographs of beautiful landscapes and people. I thought that the most beautiful pictures were made at art academies, so I applied there. At that time Düsseldorf was the only art academy in Germany with a photography class. I applied with my twenty most beautiful slides, and strangely enough Bernd (Becher) took me.

I was completely shocked when I saw Bernd and Hilla’s photographs the first time—I thought they were boring industrial photographs, the complete opposite of my visual world. I was so shocked that I couldn’t work. The friends I made at the art academy were painters and sculptors. I started to look at art and realized my idea of images was the kitsch thing; the true thing was the Bechers. Bernd said to me, “Thomas, these are not your own images. They are imitations of things you have seen. They don’t come from your soul. But I accepted you because you use color in such a beautiful way.” I really believed the documentary photograph could capture reality. My heroes were Bernd and Hilla Becher, Walker Evans, the FSA photographers, Steven Shore, Joel Meyerowitz, just to name a few.

Vicki Goldberg (Rail): Were the photographs of interiors taken in that documentary spirit?

Ruff: I didn’t change anything. I only used light that came through the windows. I started doing interiors in black and white, then changed into color. The students in the Becher class said I couldn’t do that because documentary photography has to be black and white. They were more doctrinaire than the Bechers. But Bernd said, “This is beautiful. You should continue in color.”

Rail: How did your subjects feel about the deadpan, emotionally uninflected, even affectless nature of the portraits that first brought you international recognition?

Ruff: The people I took the portraits of were very happy with them. They were all proud. As I started that project during my time in the academy, I showed the first four portraits at the Rundgang, the end-of-the-year student show. Nobody said, “I don’t want to be photographed” when I asked them. It was just obvious for us to do it in that way. We had all read 1984 by George Orwell and were wondering, How will that year be in comparison to Orwell’s visions? We knew we lived in an industrialized society where you can find surveillance cameras everywhere; we looked at the camera in a very conscious way, with the knowledge that we are watched.

If you look at a portrait of a person, it can’t give you any information about the life of the sitter, like, is he going to have a visit from his mother in two hours? So what kind of information can a photograph deliver? I have no idea of what kind of information a portrait can convey. I think the possibilities of a photographic portrait are very limited. If there are photographers who say their portraits give more information than mine, I say they only pretend.

When you take a portrait of a little girl laughing, it tells that the girl is happy. What else? It doesn’t tell us that she loves her parents. We can only guess that she must and they’re good to her. Maybe she’s living with her grandparents because her parents are dead.

[August] Sander had this kind of sociological project of society: the boss, the employee, the worker, the farmer, the craftsman, all these kinds of professions, at a time when the differentiation had started to disappear, more or less. He really thought he could capture them and make a sociological encyclopedia about his time. When I started the portraits I excluded that immediately, [the implication that] if somebody’s wearing a worker’s clothes he’s a worker, if he is wearing a suit he is an employee. The dress code has changed so much; there is no recognizable code any more. I decided to concentrate on the face because that’s the most expressionistic part of the whole person.

When I made the portraits I thought, “We are all even, equal, nobody is more important than anybody else, and at the same time everybody is unique.” I wanted to treat all my friends equally, but I was conscious that every one of my friends is unique. Twenty years ago I said photography can only capture the surface of things. It cannot go beyond the skin of a person.

Rail: Do you still feel that?

Ruff: Sometimes yes, sometimes no. The portraits are about mediated images, about photographic portraits, but at the same time it’s the person portrayed.

Rail: There is something stark in the clarity and isolation of those faces.

Ruff: If I make portraits, you can see only faces; if houses, only houses; stars with no planets or astronauts, pure stars…

It was very convenient to do the portraits because it happened in the studio, where you have no factors distracting you from the work. When you take a photograph outside of the studio, you have to depend on the weather and the circumstances of the motive, as cars could be parked in front of a house you want to photograph, or trees could be in the way, or other problems appear. As I was more interested in the image of the house than in photographing it in a documentary way, I waited until I had the right circumstances. But even so I had to manipulate two images out of the thirty I took.

My idea was architectural photography questioning the nature of reality. It wasn’t really a deliberate decision. It came from my everyday life. I was nineteen or twenty when I did the interiors. I had left my parents’ home. The work was probably about leaving home.

When I settled in Düsseldorf, my new friends studied at the academy also. I didn’t know old people or babies, so it was obvious [from the portraits] that I chose my nearest acquaintances. Then I worked on the image of architecture, the architecture surrounding my generation when I grew up. So it all was autobiographical.

Rail: You have also investigated the subject of architecture and modernism in your photographs of Mies’s buildings.

Ruff: At the end of the 1980s, I said in an interview that I can never photograph a Mies van der Rohe house because it’s already so beautiful. Mies is too big. That was pure egoism. Fifteen years later I thought I could make it up with him. When I did the Mies series, I was not afraid of his strength any more. I was able to change some of his architecture and its surroundings. I took away the color of the brick, made the sky flat, pale blue, so it looks like those awful 1950s social buildings where the big ideal was a Mies building from the 1920s. I treated not the buildings but the image of the buildings. Some of the interiors are a kind of psychedelic room. If he inhales, he gets a kind of flash, but only for a couple of seconds.

Rail: You worked from archival photographs, appropriating, as you often do.

Ruff: I didn’t have the time to go to Stuttgart, and in Berlin the situation was that I could not take photographs of the buildings at all, so I asked Terry Riley to send me archival photos. I colored them; I was sampling.

Appropriation developed into sampling. Sometimes you could say I’m appropriating, or sometimes I’m sampling. Using one image is appropriation, two or more is sampling. When I appropriate, I’m not questioning authority. It’s more pragmatic. When I did the stars [large pictures of the night skies, originally taken by astronomers] I realized I don’t have the equipment or the technology for taking the photographs myself. The work of taking the image should always be done by the most professional people. I’m professional with an 8×10 or a 4×5.

Rail: Didn’t you think about becoming a professional astronomer at one time?

Ruff: I had a telescope when I was fourteen. Photography and astronomy were my two high-school interests. I had to decide which [to concentrate on]. The stars were personal favorites of mine.

Rail: In the series of Anderes Porträts (Other Portraits) in 1995, you used a montage unit from a police history collection to superimpose two of your earlier portraits on top of one another and photograph the result. What was the impulse for this?

Ruff: When I started them, I wanted to reconstruct one of my portraits. Some critics wrote about my portraits that they were anti-individualistic and anonymous. I wanted to prove that the people depicted in my portraits are unique. It was important to me to make the Anderes Porträts in an analog way. I used a kit that the police use to build mug shots. I realized that I couldn’t reconstruct one of my portraits by matching parts [of the face]. But as I had the possibility to work with this kit, I said, “Okay, let’s do new faces that do not exist, in an analog, old-fashioned way.” I was altering photographic images but in an old fashioned way. There’s been such a lot of manipulation since the early days of photography; it didn’t start with the tool Photoshop. Just look at all those images with Stalin—who is still there and who has disappeared.

I wanted to give the viewer a chance to recognize that he’s standing in front of a manipulated image. I never made a secret out of my technical apparatus. Some photographers make a secret out of their technique. They’re afraid people could imitate it. Everybody should have the same basis and the same kind of technical opportunity. [An Anderes Porträt is] a new face, believable, but if you see the manipulation, you realize it’s an artificial face. I believe in my photographs.

Rail: In a way, you believe in the artificiality of your photographs. And what about the montages [a series of posters, mostly on political subjects]?

Ruff: (Laughs) I was trying to do something impossible. It was obvious that it’s completely stupid in a way to do montages. It’s not contemporary at all. Of course an artist’s comment on political decisions or disasters is also completely stupid, and to do this kind of work is stupid. But at the same time, I had a lot of fun. They look like bad posters for B movies, but politicians behave like actors in B movies.

Rail: The news photographs you showed are straight enough, and again they are appropriated.

Ruff: If I’d taken them, they never would have been printed.

Rail: What was your interest in photojournalism?

Ruff: I was collecting newspaper images for about ten years. At first I collected portraits, as I was working on the portraits, and I was interested in how other photographers did them. Then I was interested in other things, and I cut out what attracted me—images from the main pages, world politics, business, sports, arts, science, and so on. When I looked at them ten years later, I thought, this is a nice stamp collection. I had the idea of showing them, but the paper would turn brown in a couple of weeks. I decided to make a reproduction and also to enlarge it, to make you see the dots, so you’d definitely see that it was already printed.