2010/2/26

The Courage of the Present (Alain Badiou)

[Originally published in Le Monde, 13 February 2010. Translated by Alberto Toscano]

Alain Badiou

The Courage of the Present

For almost thirty years, the present, in our country, has been a disoriented time. I mean a time that does not offer its youth, especially the youth of the popular classes, any principle to orient existence. What is the precise character of this disorientation? One of its foremost operations consists in always making illegible the previous sequence, that sequence which was well and truly oriented. This operation is characteristic of all reactive, counter-revolutionary periods, like the one we’ve been living through ever since the end of the seventies. We can for example note that the key feature of the Thermidorean reaction, after the plot of 9 Thermidor and the execution without trial of the Jacobin leaders, was to make illegible the previous Robespierrean sequence: its reduction to the pathology of some blood-thirsty criminals impeded any political understanding. This view of things lasted for decades, and it aimed lastingly to disorient the people, which was considered to be, as it always is, potentially revolutionary.

To make a period illegible is much more than to simply condemn it. One of the effects of illegibility is to make it impossible to find in the period in question the very principles capable of remedying its impasses. If the period is declared to be pathological, nothing can be extracted from it for the sake of orientation, and the conclusion, whose pernicious effects confront us every day, is that one must resign oneself to disorientation as a lesser evil. Let us therefore pose, with regard to a previous and visibly closed sequence of the politics of emancipation, that it must remain legible for us, independently of the final judgment about it.

In the debate concerning the rationality of the French Revolution during the Third Republic, Clemenceau produced a famous formula: ‘The French Revolution forms a bloc’. This formula is noteworthy because it declares the integral legibility of the process, whatever the tragic vicissitudes of its unfolding may have been. Today, it is clear that it is with reference to communism that the ambient discourse transforms the previous sequence into an opaque pathology. I take it upon myself therefore to say that the communist sequence, including all of its nuances, in power as well as in opposition, which lay claim to the same idea, also forms a bloc.

So what can the principle and the name of a genuine orientation be today? I propose that we call it, faithfully to the history of the politics of emancipation, the communist hypothesis. Let us note in passing that our critics want to scrap the word ‘communism’ under the pretext that an experience with state communism, which lasted seventy years, failed tragically. What a joke! When it’s a question of overthrowing the domination of the rich and the inheritance of power, which have lasted millennia, their objections rest on seventy years of stumbling steps, violence and impasses! Truth be told, the communist idea has only traversed an infinitesimal portion of the time of its verification, of its effectuation. What is this hypothesis? It can be summed up in three axioms.

First, the idea of equality. The prevalent pessimistic idea, which once again dominates our time, is that human nature is destined to inequality; that it’s of course a shame that this is so, but that once we’ve shed a few tears about this, it is crucial to grasp this and accept it. To this view, the communist idea responds not exactly with the proposal of equality as a programme – let us realize the deep-seated equality immanent to human nature – but by declaring that the egalitarian principle allows us to distinguish, in every collective action, that which is in keeping with the communist hypothesis, and therefore possesses a real value, from that which contradicts it, and thus throws us back to an animal vision of humanity.

Then we have the conviction that the existence of a separate coercive state is not necessary. This is the thesis, shared by anarchists and communists, of the withering-away of the state. There have existed societies without the state, and it is rational to postulate that there may be others in the future. But above all, it is possible to organize popular political action without subordinating it to the idea of power, representation within the state, elections, etc. The liberating constraint of organized action can be exercised outside the state. There are many examples of this, including recent ones: the unexpected power of the movement of December 1995 delayed by several years anti-popular measures on pensions. The militant action of undocumented workers did not stop a host of despicable laws, but it has made it possible for these workers to be recognized as a part of our collective and political life.

A final axiom: the organization of work does not imply its division, the specialization of tasks, and in particular the oppressive differentiation between intellectual and manual labour. It is necessary and possible to aim for the essential polymorphousness of human labour. This is the material basis of the disappearance of classes and social hierarchies. These three principles do not constitute a programme; they are maxims of orientation, which anyone can use as a yardstick to evaluate what he or she says and does, personally or collectively, in its relation to the communist hypothesis.

The communist hypothesis has known two great stages, and I propose that we’re entering into a third phase of its existence. The communist hypothesis established itself on a vast scale between the 1848 revolutions and the Paris Commune (1871). The dominant themes then were those of the workers’ movement and insurrection. Then there was a long interval, lasting almost forty years (from 1871 to 1905), which corresponds to the apex of European imperialism and the systematic plunder of numerous regions of the planet. The sequence that goes from 1905 to 1976 (Cultural Revolution in China) is the second sequence of the effectuation of the communist hypothesis. Its dominant theme is the theme of the party, accompanied by its main (and unquestionable) slogan: discipline is the only weapon of those who have nothing. From 1976 to today, there is a second period of reactive stabilization, a period in which we still live, during which we have witnessed the collapse of the single-party socialist dictatorships created in the second sequence.

I am convinced that a third historical sequence of the communist hypothesis will inevitably open up, different from the two previous ones, but paradoxically closer to the first than the second. This sequence will share with the sequence that prevailed in the nineteenth century that fact that what is at stake in it is the very existence of the communist hypothesis, which today is almost universally denied. It is possible to define what, along with others, I am attempting as preliminary efforts aimed at the reestablishment of the communist hypothesis and the deployment of its third epoch.

What we need, in these early days of the third sequence of existence of the communist hypothesis, is a provisional morality for a disoriented time. It’s a matter of minimally maintaining a consistent subjective figure, without being able to rely on the communist hypothesis, which has yet to be re-established on a grand scale. It is necessary to find a real point to hold, whatever the cost, an ‘impossible’ point that cannot be inscribed in the law of the situation. We must hold a real point of this type and organize its consequences.

The living proof that our societies are obviously in-human is today the foreign undocumented worker: he is the sign, immanent to our situation, that there is only one world. To treat the foreign proletarian as though he came from another world, that is indeed the specific task of the ‘home office’ (ministère de l'identité nationale), which has its own police force (the ‘border police’). To affirm, against this apparatus of the state, that any undocumented worker belongs to the same world as us, and to draw the practical, egalitarian and militant consequences of this – that is an example of a type of provisional morality, a local orientation in keeping with the communist hypothesis, amid the global disorientation which only its reestablishment will be able to counter.

The principal virtue that we need is courage. This is not always the case: in other circumstances, other virtues may have priority. For instance, during the revolutionary war in China, Mao promoted patience as the cardinal virtue. But today, it is undeniably courage. Courage is the virtue that manifests itself, without regard for the laws of the world, by the endurance of the impossible. It’s a question of holding the impossible point without needing to account for the whole of the situation: courage, to the extent that it’s a matter of treating the point as such, is a local virtue. It partakes of a morality of the place, and its horizon is the slow reestablishment of the communist hypothesis.

http://www.cinestatic.com/infinitethought/2010/02/badiou-op-ed-courage-of-present.asp

Judith Butler on the Jewishness and cultural boycott.

Philosopher, professor and author Judith Butler arrived in Israel this month, en route to the West Bank, where she was to give a seminar at Bir Zeit University, visit the theater in Jenin, and meet privately with friends and students. A leading light in her field, Butler chose not to visit any academic institutions in Israel itself. In the conversation below, conducted in New York several months ago, Butler talks about gender, the dehumanization of Gazans, and how Jewish values drove her to criticize the actions of the State of Israel. In Israel, people know you well. Your name was even in the popular film Ha-Buah [The Bubble - the tragic tale of a gay relationship between an Israeli Jew and a Palestinian Muslim]. [laughs] Although I disagreed with the use of my name in that context. I mean, it was very funny to say, "don't Judith Butler me," but "to Judith Butler someone" meant to say something very negative about men and to identify with a form of feminism that was against men. And I've never been identified with that form of feminism. That?s not my mode. I'm not known for that. So it seems like it was confusing me with a radical feminist view that one would associate with Catharine MacKinnon or Andrea Dworkin, a completely different feminist modality. I'm not always calling into question who's a man and who's not, and am I a man? Maybe I'm a man. [laughs] Call me a man. I am much more open about categories of gender, and my feminism has been about women's safety from violence, increased literacy, decreased poverty and more equality. I was never against the category of men. A beautiful Israeli poem asks, "How does one become Avot Yeshurun?" Avot Yeshurun was a poet who caused turmoil in Israeli poetry. I want to ask, how does one become Judith Butler -especially with the issue of Gender Trouble, the book that so troubled the discourse on gender? You know, I'm not sure that I know how to give an account of it, and I think it troubles gender differently depending on how it is received and translated. For instance, one of the first receptions [of the book] was in Germany, and there, it seemed very clear that young people wanted a politics that emphasized agency, or something affirmative that they could create or produce. The idea of performativity - which involved bringing categories into being or bringing new social realities about - was very exciting, especially for younger people who were tired with old models of oppression - indeed, the very model men oppress women, or straights oppress gays. It seemed that if you were subjugated, there were also forms of agency that were available to you, and you were not just a victim, or you were not only oppressed, but oppression could become the condition of your agency. Certain kinds of unexpected results can emerge from the situation of oppression if you have the resources and if you have collective support. It's not an automatic response; it's not a necessary response. But it's possible. I think I also probably spoke to something that was already happening in the movement. I put into theoretical language what was already being impressed upon me from elsewhere. So I didn't bring it into being single-handedly. I received it from several cultural resources and put it into another language. Once you became "Judith Butler," we began to hear more about Jews and Jewish texts. People came to hear you speak about gender and suddenly they were faced with Gaza, divine violence. It almost felt like you had some closure on the previous matter. Is there a connection, a continuum, or is this a new phase? Let's go back further. I'm sure I've told you that I began to be interested in philosophy when I was 14, and I was in trouble in the synagogue. The rabbi said, "You are too talkative in class. You talk back, you are not well behaved. You have to come and have a tutorial with me." I said "OK, great!" I was thrilled. He said: "What do you want to study in the tutorial? This is your punishment. Now you have to study something seriously." I think he thought of me as unserious. I explained that I wanted to read existential theology focusing on Martin Buber. (I've never left Martin Buber.) I wanted look at the question of whether German idealism could be linked with National Socialism. Was the tradition of Kant and Hegel responsible in some way for the origins of National Socialism? My third question was why Spinoza was excommunicated from the synagogue. I wanted to know what happened and whether the synagogue was justified. Now I must go Jewish: what was your parents' relation to Judaism? My parents were practicing Jews. My mother grew up in an orthodox synagogue and after my grandfather died, she went to a conservative synagogue and a little later ended up in a reform synagogue. My father was in reform synagogues from the beginning. My mother's uncles and aunts were all killed in Hungary [during the Holocaust]. My grandmother lost all of her relatives, except for the two nephews who came with them in the car when my grandmother went back in 1938 to see who she could rescue. It was important for me. I went to Hebrew school. But I also went after school to special classes on Jewish ethics because I was interested in the debates. So I didn't do just the minimum. Through high school, I suppose, I continued Jewish studies alongside my public school education. And you showed me the photos of the bar mitzvah of your son as a good proud Jewish Mother... So it's been there from the start, it's not as if I arrived at some place that I haven't always been in. I grew very skeptical of certain kind of Jewish separatism in my youth. I mean, I saw the Jewish community was always with each other; they didn't trust anybody outside. You'd bring someone home and the first question was "Are they Jewish, are they not Jewish?" Then I entered into a lesbian community in college, late college, graduate school, and the first thing they asked was, "Are you a feminist, are you not a feminist?" "Are you a lesbian, are you not a lesbian?" and I thought "Enough with the separatism!" It felt like the same kind of policing of the community. You only trust those who are absolutely like yourself, those who have signed a pledge of allegiance to this particular identity. Is that person really Jewish, maybe they're not so Jewish. I don?t know if they're really Jewish. Maybe they're self-hating. Is that person lesbian? I think maybe they had a relationship with a man. What does that say about how true their identity was? I thought I can't live in a world in which identity is being policed in this way. But if I go back to your other question... In Gender Trouble, there is a whole discussion of melancholy. What is the condition under which we fail to grieve others? I presumed, throughout my childhood, that this was a question the Jewish community was asking itself. It was also a question that I was interested in when I went to study in Germany. The famous Mitscherlich book on the incapacity to mourn, which was a criticism of German post-war culture, was very, very interesting to me. In the 70s and 80s, in the gay and lesbian community, it became clear to me that very often, when a relationship would break up, a gay person wouldn't be able to tell their parents, his or her parents. So here, people were going through all kinds of emotional losses that were publicly unacknowledged and that became very acute during the AIDS crisis. In the earliest years of the AIDS crisis, there were many gay men who were unable to come out about the fact that their lovers were ill, A, and then dead, B. They were unable to get access to the hospital to see their lover, unable to call their parents and say, "I have just lost the love of my life." This was extremely important to my thinking throughout the 80s and 90s. But it also became important to me as I started to think about war. After 9/11, I was shocked by the fact that there was public mourning for many of the people who died in the attacks on the World Trade Center, less public mourning for those who died in the attack on the Pentagon, no public mourning for the illegal workers of the WTC, and, for a very long time, no public acknowledgment of the gay and lesbian families and relationships that had been destroyed by the loss of one of the partners in the bombings. Then we went to war very quickly, Bush having decided that the time for grieving is over. I think he said that after ten days, that the time for grieving is over and now is time for action. At which point we started killing populations abroad with no clear rationale. And the populations we targeted for violence were ones that never appeared to us in pictures. We never got little obituaries for them. We never heard anything about what lives had been destroyed. And we still don't. I then moved towards a different kind of theory, asking under what conditions certain lives are grievable and certain lives not grievable or ungrievable. It's clear to me that in Israel-Palestine and in the violent conflicts that have taken place over the years, there is differential grieving. Certain lives become grievable within the Israeli press, for instance - highly grievable and highly valuable - and others are understood as ungrievable because they are understood as instruments of war, or they are understood as outside the nation, outside religion, or outside that sense of belonging which makes for a grievable life. The question of grievability has linked my work on queer politics, especially the AIDS crisis, with my more contemporary work on war and violence, including the work on Israel-Palestine. It's interesting because when the war on Gaza started, I couldn't stay in Tel Aviv anymore. I visited the Galilee a lot. And suddenly I realized that many of the Palestinians who died in Gaza have families there, relatives who are citizens of Israel. What people didn't know is that there was a massed grief in Israel. Grief for families who died in Gaza, a grief within Israel, of citizens of Israel. And nobody in the country spoke about it, about the grief within Israel. It was shocking. The Israeli government and the media started to say that everyone who was killed or injured in Gaza was a member of Hamas; or that they were all being used as part of the war effort; that even the children were instruments of the war effort; that the Palestinians put them out there, in the targets, to show that Israelis would kill children, and this was actually part of a war effort. At this point, every single living being who is Palestinian becomes a war instrument. They are all, in their being, or by virtue of being Palestinian, declaring war on Israel or seeking the destruction of the Israel. So any and all Palestinian lives that are killed or injured are understood no longer to be lives, no longer understood to be living, no longer understood even to be human in a recognizable sense, but they are artillery. The bodies themselves are artillery. And of course, the extreme instance of that is the suicide bomber, who has become unpopular in recent years. That is the instance in which a body becomes artillery, or becomes part of a violent act. If that figure gets extended to the entire Palestinian population, then there is no living human population anymore, and no one who is killed there can be grieved. Because everyone who is a living Palestinian is, in their being, a declaration of war, or a threat to the existence of Israel, or pure military artillery, materiel. They have been transformed, in the Israeli war imaginary, into pure war instruments. So when a people who believes that another people is out to destroy them sees all the means of destruction killed, or some extraordinary number of the means of destruction destroyed, they are thrilled, because they think their safety and well-being and happiness are being purchased, are being achieved through this destruction. And what happened with the perspective from the outside, the outside media, was extremely interesting to me. The European press, the U.S. press, the South American press, the East Asian press all raised questions about the excessive violence of the Gaza assault. It was very strange to see how the Israeli media made the claim that people on the outside do not understand; that people on the outside are anti-Semitic; that people on the outside are blaming Israel for defending themselves when they themselves, if attacked, would do the exact same thing. Why Israel-Palestine? Is this directly connected to your Jewishness? As a Jew, I was taught that it was ethically imperative to speak up and to speak out against arbitrary state violence. That was part of what I learned when I learned about the Second World War and the concentration camps. There were those who would and could speak out against state racism and state violence, and it was imperative that we be able to speak out. Not just for Jews, but for any number of people. There was an entire idea of social justice that emerged for me from the consideration of the Nazi genocide. I would also say that what became really hard for me is that if one wanted to criticize Israeli state violence - precisely because that as a Jew one is under obligation to criticize excessive state violence and state racism - then one is in a bind, because one is told that one is either self-hating as a Jew or engaging anti-Semitism. And yet for me, it comes out of a certain Jewish value of social justice. So how can I fulfill my obligation as a Jew to speak out against an injustice when, in speaking out against Israeli state and military injustice, I am accused of not being a good enough Jew or of being a self-hating Jew? This is the bind of my current situation. Let me say one other thing about Jewish values. There are two things I took from Jewish philosophy and my Jewish formation that were really important for me... well there are many. There are many. Sitting shiva, for instance, explicit grieving. I thought it was the one of the most beautiful rituals of my youth. There were several people who died in my youth, and there were several moments when whole communities gathered in order to make sure that those who had suffered terrible losses were taken up and brought back into the community and given a way to affirm life again. The other idea was that life is transient, and because of that, because there is no after world, because we don't have any hopes in a final redemption, we have to take especially good care of life in the here and now. Life has to be protected. It is precarious. I would even go so far as to say that precarious life is, in a way, a Jewish value for me. I realized something, through your way of thinking. A classic mistake that people made with Gender Trouble was the notion that body and language are static. But everything is in dynamic and in constant movement; the original never exists. In a way I felt the same with the Diaspora and the emancipation. Neither are static. No one came before the other. The Diaspora, when it was static, became separatist, became the shtetl. And when the emancipation was realized, it became an ethnocratic state; it also became separatist, a re-construction of the ghetto. So maybe the tension between the two, emancipation and Diaspora, without choosing a one or the other, is the only way to keep us out of ethnocentrism. I suppose my idea is not yet fully formulated. It relates to the way I felt that my grandfather was open to the language of exile while being connected to the land at the same time. By being open to both, emancipation and Diaspora, we might avoid falling into ethnocentrism. You have a tension between Diaspora and emancipation. But what I am thinking of is perhaps something a little different. I have to say, first of all, that I do not think that there can be emancipation with and through the establishment of state that restricts citizenship in the way that it does, on the basis of religion? So in my view, any effort to retain the idea of emancipation when you don't have a state that extends equal rights of citizenship to Jews and non-Jews alike is, for me, bankrupt. It's bankrupt. That's why I would say that there should be bi-nationalism from the beginning. Or even multi-nationalism. Maybe even a kind of citizenship without regard to religion, race, ethnicity, etc. In any case, the more important point here is that there are those who clearly believe that Jews who are not in Israel, who are in the Galut, are actually either in need of return ? they have not yet returned, or they are not and cannot be representative of the Jewish people. So the question is: what does it mean to transform the idea of Galut into Diaspora? In other words, Diaspora is another tradition, one that involves the scattering without return. I am very critical of this idea of return, and I think "Galut" very often demeans the Diasporic traditions within Judaism. I thought that if we make a film about bi-nationalism, the opening scene should be a meeting of "The First Jewish Congress for Bi-Nationalism." It could be a secret meeting in which we all discuss who we would like to be our first president, and the others there send me to choose you? because we need to have a woman, and she has to be queer. But not only queer, and not only woman. She has to be the most important Jewish philosopher today. But seriously, you know, it would be astonishing to think about what forms of political participation would still be possible on a model of federal government. Like a federated authority for Palestine-Israel that was actually governed by a strong constitution that guaranteed rights regardless of cultural background, religion, ethnicity, race, and the rest. In a way, bi-nationalism goes part of the way towards explaining what has to happen. And I completely agree with you that there has to be a cultural movement that overcomes hatred and paranoia and that actually draws on questions of cohabitation. Living in mixity and in diversity, accepting your neighbor, finding modes of living together. And no political solution, at a purely procedural level, is going to be successful if there is no bilingual education, if there are no ways of reorganizing neighborhoods, if there are no ways of reorganizing territory, bringing down the wall, accepting the neighbors you have, and accepting that there are profound obligations that emerge from being adjacent to another people in this way. So I agree with you. But I think we have to get over the idea that a state has to express a nation. And if we have a bi-national state, it's expressing two nations. Only when bi-nationalism deconstructs the idea of a nation can we hope to think about what a state, what a polity might look like that would actually extend equality. It is no longer the question of "two peoples," as Martin Buber put it. There is extraordinary complexity and intermixing among both the Jewish and the Palestinian populations. There will be those who say, "Ok, a state that expresses two cultural identities." No. State should not be in the business of expressing cultural identity. Why do we use term "bi-nationalism?" For me it is the beginning of a process, not the end. We could say "multi-nationalism," or "one-state solution." Why do we prefer to use the term "bi-nationalism" rather than "one state" now? I believe that people have reasonable fears that a one-state solution would ratify the existing marginalization and impoverishment of the Palestinian people. That Palestine would be forced to accept a kind of Bantustan existence. Or vice versa, for the Jews. | ||||||||

Now I want to move to the last part of the conversation. It was over three years ago, at the beginning of the Second Lebanon war, that Slavoj Žižek came to Israel to give a speech on my film Forgiveness. The Campaign for the Academic and Cultural Boycott of Israel asked him not to come to the Jerusalem Film Festival. They said that I should show my film - as Israelis shouldn't boycott Israel, but they asked international figures to boycott the festival. Žižek, who was the subject of one of the films in the festival, said he would not speak about that film. But he asked: why not support the opposition in Israel by speaking about Forgiveness? They answered that he could support the opposition, but not in an official venue. He did not know what to do. Žižek chose to ask for your advice. Your position then, if I recall correctly, was that it was most important to exercise, solidarity with colleagues who chose nonviolent means of resistance and that it was a mistake to take money from Israeli cultural institutions. Your suggestion to Žižek was that he speak about the film without being a guest of the festival. He gave back the money and announced that he was not a guest. There was no decision about endorsing or not endorsing a boycott. For me, at the time, the concept of cultural boycott was kind of shocking, a strange concept. The movement has since grown a lot, and I know that you've done a lot of thinking about it. I wonder what do you think about this movement now, the full Boycott, Diversion and Sanction movement (BDS), three years after that confusing event? I think that the BDS movement has taken several forms, and it is probably important to distinguish among them. I would say that around six or seven years ago, there was a real confusion about what was being boycotted, what goes under the name of "boycott." There were some initiatives that seemed to be directed against Israeli academics, or Israeli filmmakers, cultural producers, or artists that did not distinguish between their citizenship and their participation, active or passive, in occupation politics. We must keep in mind that the BDS movement has always been focused on the occupation. It is not a referendum on Zionism, and it does not take an explicit position on the one-state or two-state solution. And then there were those who sought to distinguish boycotting individual Israelis from boycotting the Israeli institutions. But it is not always easy to know how to make the distinction between who is an individual and who is an institution. And I think a lot of people within the U.S. and Europe just backed away, thinking that it was potentially discriminatory to boycott individuals or, indeed, institutions on the basis of citizenship, even though many of those who were reluctant very much wanted to find a way to support a non-violent resistance to the occupation. But now I feel that it has become more possible, more urgent to reconsider the politics of the BDS. It is not that the principles of the BDS have changed: they have not. But there are now ways to think about implementing the BDS that keep in mind the central focus: any event, practice, or institution that seeks to normalize the occupation, or presupposes that "ordinary" cultural life can continue without an explicit opposition to the occupation is itself complicit with the occupation. We can think of this as passive complicity, if you like. But the main point is to challenge those institutions that seek to separate the occupation from other cultural activities. The idea is that we cannot participate in cultural institutions that act as if there is no occupation or that refuse to take a clear and strong stand against the occupation and dedicate their activities to its undoing So, with this in mind, we can ask, what does it mean to engage in boycott? It means that, for those of us on the outside, we can only go to an Israeli institution, or an Israeli cultural event, in order to use the occasion to call attention to the brutality and injustice of the occupation and to articulate an opposition to it. I think that's what Naomi Klein did, and I think it actually opened up another route for interpreting the BDS principles. It is no longer possible for me to come to Tel Aviv and talk about gender, Jewish philosophy, or Foucault, as interesting as that might be for me; it is certainly not possible to take money from an organization or university or a cultural organization that is not explicitly and actively anti-occupation, acting as if the cultural event within Israeli borders was not happening against the background of occupation? Against the background of the assault on, and continuing siege of, Gaza? It is this unspoken and violent background of "ordinary" cultural life that needs to become the explicit object of cultural and political production and criticism. Historically, I see no other choice, since affirming the status quo means affirming the occupation. One cannot "set aside" the radical impoverishment, the malnutrition, the limits on mobility, the intimidation and harassment at the borders, and the exercise of state violence in both Gaza and the West Bank and talk about other matters in public? If one were to talk about other matters, then one is actively engaged in producing a limited public sphere of discourse which has the repression and, hence, continuation of violence as its aim. Let us remember that the politics of boycott are not just matters of "conscience" for left intellectuals within Israel or outside. The point of the boycott is to produce and enact an international consensus that calls for the state of Israel to comply with international law. The point is to insist on the rights of self-determination for Palestinians, to end the occupation and colonization of Arab lands, to dismantle the Wall that continues the illegal seizure of Palestinian land, and to honor several UN resolutions that have been consistently defied by the Israeli state, including UN resolution 194, which insists upon the rights of refugees from 1948. So, an approach to the cultural boycott in particular would have to be one that opposes the normalization of the occupation in order to bring into public discourse the basic principles of injustice at stake. There are many ways to articulate those principles, and this is where intellectuals are doubtless under a political obligation to become innovative, to use the cultural means at our disposal to make whatever interventions we can. The point is not simply to refuse contact and forms of cultural and monetary exchange - although sometimes these are most important - but rather, affirmatively, to lend one's support to the strongest anti-violent movement against the occupation that not only affirms international law, but establishing exchanges with Palestinian cultural and academic workers, cultivating international consensus on the rights of the Palestinian people, but also altering that hegemonic presumption within the global media that any critique of Israel is implicitly anti-democratic or anti-Semitic. Surely it has always been the best part of the Jewish intellectual tradition to insist upon the ethical relation to the non-Jew, the extension of equality and justice, and the refusal to keep silent in the face of egregrious wrongs. I want to share with you what Riham Barghouti, from BDS New York, told me. She said that, for her, BDS is a movement for everyone who supports the end of the occupation, equal rights for the Palestinians of 1948, and the moral and legal demand of the Palestinians' right of return. She suggested that each person who is interested, decide how much of the BDS spectrum he or she is ready to accept. In other words, endorsement of the boycott movement is a continuous decision, not a categorical one. Just don't tell us what our guidelines are. You can agree with our principles, join the movement, and decide on the details on your own. Yes, well, one can imagine a bumper sticker: "what part of 'justice' do you fail to understand?" It is surely important that many prominent Israelis have begun to accept part of the BDS principles, and this may well be an incremental way to make the boycott effort more understandable. But it may also be important to ask, why is it that so many left [wing] Israelis have trouble entering into collaborative politics with Palestinians on the issue of the boycott, and why is it that the Palestinian formulations of the boycott do not form the basis for that joint effort? After all, the BDS call has been in place since 2005; it is an established and growing movement, and the basic principles have been worked out. Any Israeli can join that movement, and they would doubtless fine that they would immediately be in greater contact with Palestinians than they otherwise would be. The BDS provides the most powerful rubric for Israeli-Palestinian cooperative actions. This is doubtless surprising and paradoxical for some, but it strikes me as historically true. It's interesting to me that very often Israelis I speak to say, "We cannot enter into collaboration with the Palestinians because they don't want to collaborate with us, and we don't blame them." Or: "We would put them in a bad position if we were to invite them to our conferences." Both of these positions presume the occupation as background, but they do not address it directly. Indeed, these kinds of positions are biding time when there is no time but now to make one's opposition known. Very often, such utterances take on a position of self-paralyzing guilt which actually keeps them from taking active and productive responsibility for opposing the occupation even more remote. Sometimes it seems to me that they make boycott politics into a question of moral conscience, which is different from a political commitment. If it is a moral issue, then "I" as an Israeli have a responsibility to speak out or against, to sink into self-beratement or become self-flagellating in public and become a moral icon. But these kinds of moral solutions are, I think, besides the point. They continue to make "Israeli" identity into the basis of the political position, which is a kind of tacit nationalism. Perhaps the point is to oppose the manifest injustice in the name of broader principles of international law and the opposition to state violence, the disenfranchisement politically and economically of the Palestinian people. If you happen to be Israeli, then unwittingly your position shows that Israelis can and do take positions in favor of justice, and that should not be surprising. But it does not make it an "Israeli" position. But let me return to the question of whether boycott politics undermines collaborative ventures, or opens them up. My wager is that the minute you come out in favor of some boycott, divestment or sanctions strategy, Udi, you will have many collaborators among Palestinians. I think many people fear that the boycott is against collaboration, but in fact Israelis have the power to produce enormous collaborative networks if they agree that they will use their public power, their cultural power, to oppose the occupation through the most powerful non-violent means available. Things change the minute you say, "We cannot continue to act as normal." Of course, I myself really want to be able to talk about novels, film, and philosophy, sometimes quite apart from politics. Unfortunately, I cannot do that in Israel now. I cannot do it until the occupation has been successfully and actively challenged. The fact is that there is no possibility of going to Israel without being used either as an example of boycott or as an example of anti-boycott. So when I went, many years ago, and the rector of Tel Aviv University said, "Look how lucky we are. Judith Butler has come to Tel Aviv University, a sign that she does not accept the boycott," I was instrumentalized against my will. And I realized I cannot function in that public space without already being defined in the boycott debate. So there is no escape from it. One can stay quiet and accept the status quo, or one can take a position that seeks to challenge the status quo. I hope one day there will be a different political condition where I might go there and talk about Hegel, but that is not possible now. I am very much looking forward to teaching at Bir Zeit in February. It has a strong gender and women's studies faculty, and I understand that the students are interested in discussing questions of war and cultural analysis. I also clearly stand to learn. The boycott is not just about saying "no" - it is also a way to give shape to one's work, to make alliances, and to insist on international norms of justice. To work to the side of the problem of the occupation is to participate in its normalization. And the way that normalization works is to efface or distort that reality within public discourse. As a result, neutrality is not an option. So we're boycotting normalization. That's what we're boycotting. We are against normalization. And you know what, there are going to be many tactics for disrupting the normalization of the occupation. Some of us will be well-equipped to intervene with images and words, and others will continue demonstrations and other forms of cultural and political statements. The question is not what your passport says (if you have a passport), but what you do. We are talking about what happens in the activity itself. Does it disrupt and contest the normalization of the occupation? You remember that in Toronto declaration against the spotlight on Tel Aviv at the film festival, it was very clear that we do not boycott individuals, but the Israeli foreign minister tried to argue that we were boycotting individuals. Yet the question is about institutions. On that note, I want to clarify: You will not speak in Tel Aviv University... forever? Well, not forever... When it's a fabulous bi-national university [laughter] Udi Aloni is an Israeli-American filmmaker and writer http://haaretz.com/hasen/spages/1152017.html | ||||||||

2010/2/20

電影旅行(3):高達之「斷了氣」

Montparnasse, Paris.

假如要選兩部電影史上最重要的作品,每個人或許意見不同、眾說紛紜,而難有定見。但我會挑維托夫的《持攝影機的人》 ,與高達的《斷了氣》。這兩部電影都顛覆了前人對影像生產的規則與想像,並提出了電影語言所獨享的運動格局。從此以後,何謂影像?怎麼敘事?這些後設命題才被人們廣泛認知,成為深刻自省的電影創作者,所不能不面對的問題意識。

《斷了氣》裡最著名的,大概就是片尾Jean-Paul Belmondo飾演的男主角在被美國女友Jean Seberg報警密告、行蹤暴露後,在一條怪異的巷弄裡被追捕警方開槍射殺,他卻自顧自地漫步數十呎,最後才精疲力竭倒下的劇情。在這個經典橋段裡,男女主角不斷面對鏡頭、兩眼直視觀眾,揭露並證成他們所費力成就的,各位所沈溺觀看的,是一個吾等再也熟悉不過的,某種關於警匪、愛情、背叛的俗套劇碼。

關於語言:不是人們在說話,而是話語藉由人們而說了出來。因此也可以說,不是演員在演電影,而是電影論述藉由作為載體的演員,而再生產了自身。因此人們會說,《斷了氣》揭露了這件事,藉此與傳統敘事決裂,因此是現代(主義)電影的開端。

這段著名的橋段,拍攝地點是巴黎Montparnasse區的Rue Campagne Première。Jean-Paul Belmondo逃出來的門房是這條路的11號(劇情演到Jean Seberg向警方通風報信時,有提到這個地址),挨槍後他一路像是跳舞般跑到右邊路底,最後不支倒下。

Rue Campagne Première, Paris.

《斷了氣》劇情裡魂歸西天的是男主角Jean-Paul Belmondo,但現實生活世界裡,他仍一尾活龍地活躍於影劇版,反倒是活得抑鬱寡歡的Jean Seberg,早在1979年便服藥自盡。她下葬於著名的Montparnasse墓園。墓園的位置,就在《斷了氣》片尾場景的隔壁一條街。走路,只有五分鐘路程。

所謂的戲如人生,或真實與虛幻的彼此滲透,大概就是這個樣子。

所謂的戲如人生,或真實與虛幻的彼此滲透,大概就是這個樣子。

Montparnasse Cemetery, Paris.

2010/2/14

The Adventure of A Photographer (Italo Calvino)

THE ADVENTURE OF A PHOTOGRAPHER

by Italo Calvino, c 1958

(trans. from Italian by William Weaver)

WHEN SPRING comes, the city’s inhabitants, by the hundreds of thousands, go out on Sundays with leather cases over their shoulders. And they photograph one another. They come back as happy as hunters with bulging game bags; they spend days waiting, with sweet anxiety, to see the developed pictures (anxiety to which some add the subtle pleasure of alchemistic manipulations in the darkroom, forbidding any intrusion by members of the family, relishing the acid smell that is harsh to the nostrils). It is only when they have the photos before their eyes that they seem to take tangible possession of the day they spent, only then that the mountain stream, the movement of the child with his pail, the glint of the sun on the wife’s legs take on the irrevocability of what has been and can no longer be doubted. Everything else can drown in the unreliable shadow of memory.

Seeing a good deal of his friends and colleagues, Antonino Paraggi, a nonphotographer, sensed a growing isolation. Every week he discovered that the conversations of those who praise the sensitivity of a filter or discourse on the number of DINs were swelled by the voice of yet another to whom he had confided until yesterday, convinced that they were shared, his sarcastic remarks about an activity that to him seemed so unexciting, so lacking in surprises.

Professionally, Antonino Paraggi occupied an executive position in the distribution department of a production firm, but his real passion was commenting to his friends on current events large and small, unraveling the thread of general causes from the tangle of details; in short, by mental attitude he was a philosopher, and he devoted all his thoroughness to grasping the significance of even the events most remote from his own experience. Now he felt that something in the essence of photographic man was eluding him, the secret appeal that made new adepts continue to join the ranks of the amateurs of the lens, some boasting of the progress of their technical and artistic skill, others, on the contrary, giving all the credit to the efficiency of the camera they had purchased, which was capable (according to them) of producing masterpieces even when operated by inept hands (as they declared their own to be, because wherever pride aimed at magnifying the virtues of mechanical devices, subjective talent accepted a proportionate humiliation). Antonino Paraggi understood that neither the one nor the other motive of satisfaction was decisive: the secret lay elsewhere.

It must be said that his examination of photography to discover the causes of a private dissatisfaction—as of someone who feels excluded from something—was to a certain extent a trick Antonino played on himself, to avoid having to consider another, more evident, process that was separating him from his friends. What was happening was this: his acquaintances, of his age, were all getting married, one after another, and starting families, while Antonino remained a bachelor.

Yet between the two phenomena there was undoubtedly a connection, inasmuch as the passion for the lens often develops in a natural, virtually physiological way as a secondary effect of fatherhood. One of the first instincts of parents, after they have brought a child into the world, is to photograph it. Given the speed of growth, it becomes necessary to photograph the child often, because nothing is more fleeting and unmemorable than a six-month-old infant, soon deleted and replaced by one of eight months, and then one of a year; and all the perfection that, to the eyes of parents, a child of three may have reached cannot prevent its being destroyed by that of the four-year-old. The photograph album remains the only place where all these fleeting perfections are saved and juxtaposed, each aspiring to an incomparable absoluteness of its own. In the passion of new parents for framing their offspring in the sights to reduce them to the immobility of black-and-white or a full color slide, the nonphotographer and non-procreator Antonino saw chiefly a phase in the race toward madness lurking in that black instrument. But his reflections on the iconography-family-madness nexus were summary and reticent: otherwise he would have realized that the person actually running the greatest risk was himself, the bachelor.

In the circle of Antonino’s friends, it was customary to spend the weekend out of town, in a group, following a tradition that for many of them dated back to their student days and that had been extended to include their girl friends, then their wives and their children, as well as wet nurses and governesses, and in some cases in-laws and new acquaintances of both sexes. But since the continuity of their habits, their getting together, had never lapsed, Antonino could pretend that nothing had changed with the passage of the years and that they were still the band of young men and women of the old days, rather than a conglomerate of families in which he remained the only surviving bachelor.

More and more often, on these excursions to the sea or the mountains, when it came time for the family group or the multi-family picture, an outsider was asked to lend a hand, a passer-by perhaps, willing to press the button of the camera already focused and aimed in the desired direction. In these cases, Antonino couldn’t refuse his services: he would take the camera from the hands of a father or a mother, who would then rush to assume his or her place in the second row, sticking his head forward between two other heads, or crouching among the little ones; and Antonino, concentrating all his strength in the finger destined for this use, would press. The first times, an awkward stiffening of his arm would make the lens veer to capture the masts of ships or the spires of steeples, or to decapitate grandparents, uncles, and aunts. He was accused of doing this on purpose, reproached for making a joke in poor taste. It wasn’t true: his intention was to lend the use of his finger as docile instrument of the collective wish, but also to exploit his temporary position of privilege to admonish both photographers and their subjects as to the significance of their actions. As soon as the pad of his finger reached the desired condition of detachment from the rest of his person and personality, he was free to communicate his theories in well-reasoned discourse, framing at the same time well-composed little groups. (A few accidental successes had sufficed to give him nonchalance and assurance with viewfinders and light meters.)

"…Because once you’ve begun," he would preach, "there is no reason why you should stop. The line between the reality that is photographed because it seems beautiful to us and the reality that seems beautiful because it has been photographed is very narrow. If you take a picture of Pierluca because he’s building a sand castle, there is no reason not to take his picture while he’s crying because the castle has collapsed, and then while the nurse consoles him by helping him find a sea shell in the sand. The minute you start saying something, ‘Ah, how beautiful! We must photograph it!’ you are already close to the view of the person who thinks that everything that is not photographed is lost, as if it had never existed, and that therefore, in order really to live, you must photograph as much as you can, and to photograph as much as you can you must either live in the most photographable way possible, or else consider photographable every moment of your life. The first course leads to stupidity; the second to madness."

"You’re the one who’s mad and stupid," his friends would say to him, "and a pain in the ass, into the bargain."

"For the person who wants to capture everything that passes before his eyes," Antonino would explain, even if nobody was listening to him any more, "the only coherent way to act is to snap at least one picture a minute, from the instant he opens his eyes in the morning to when he goes to sleep. This is the only way that the rolls of exposed film will represent a faithful diary of our days, with nothing left out. If I were to start taking pictures, I’d see this thing through, even if it meant losing my mind. But the rest of you still insist on making a choice. What sort of choice? A choice in the idyllic sense, apologetic, consolatory, at peace with nature, the fatherland, the family. Your choice isn’t only photographic; it is a choice of life, which leads you to exclude dramatic conflicts, the knots of contradiction, the great tensions of will, passion, aversion. So you think you are saving yourselves from madness, but you are falling into mediocrity, into hebetude."

A girl named Bice, someone’s ex-sister-in-law, and another named Lydia, someone else’s ex-secretary, asked him please to take a snapshot of them while they were playing ball among the waves. He consented, but since in the meanwhile he had worked out a theory in opposition to snapshots, he dutifully expressed it to the two friends:

"What drives you two girls to cut from the mobile continuum of your day these temporal slices, the thickness of a second? Tossing the ball back and forth, you are living in the present, but the moment the scansion of the frames is insinuated between your acts it is no longer the pleasure of the game that motivated you but, rather, that of seeing yourselves again in the future, of rediscovering yourselves in twenty years’ time, on a piece of yellowed cardboard (yellowed emotionally, even if modern printing procedures will preserve it unchanged). The taste for the spontaneous, natural, lifelike snapshot kills spontaneity, drives away the present. Photographed reality immediately takes on a nostalgic character, of joy fled on the wings of time, a commemorative quality, even if the picture was taken the day before yesterday. And the life that you live in order to photograph it is already, at the outset, a commemoration of itself. To believe that the snapshot is more true than the posed portrait is a prejudice…"

So saying, Antonino darted around the two girls in the water, to focus on the movements of their game and cut out of the picture the dazzling glints of the sun on the water. In a scuffle for the ball, Bice, flinging herself on the other girl, who was submerged, was snapped with her behind in close-up, flying over the waves. Antonino, so as not to lose this angle, had flung himself back in the water while holding up the camera, nearly drowning.

"They all came out well, and this one’s stupendous," they commented a few days later, snatching the proofs from each other. They had arranged to meet at the photography shop. "You’re good; you must take some more of us."

Antonino had reached the conclusion that it was necessary to return to posed subjects, in attitudes denoting their social position and their character, as in the nineteenth century. His antiphotographic polemic could be fought only from within the black box, setting one kind of photography against another.

"I’d like to have one of those old box cameras," he said to his girl friends, "the kind you put on a tripod. Do you think it’s still possible to find one?"

"Hmm, maybe at some junk shop…"

"Let’s go see."

The girls found it amusing to hunt for this curious object; together they ransacked flea markets, interrogated old street photographers, followed them to their lairs. In those cemeteries of objects no longer serviceable lay wooden columns, screens, backdrops with faded landscapes; everything that suggested an old photographer’s studio, Antonino bought. In the end he managed to get hold of a box camera, with a bulb to squeeze. It seemed in perfect working order. Antonino also bought an assortment of plates. With the girls helping him, he set up the studio in a room of his apartment, all fitted out with old-fashioned equipment, except for two modern spotlights.

Now he was content. "This is where to start," he explained to the girls. "In the way our grandparents assumed a pose, in the convention that decided how groups were to be arranged, there was a social meaning, a custom, a taste, a culture. An official photograph, or one of a marriage or a family or a school group, conveyed how serious and important each role or institution was, but also how far they were all false or forced, authoritarian, hierarchical. This is the point: to make explicit the relationship with the world that each of us bears within himself, and which today we tend to hide, to make unconscious, believing that in this way it disappears, whereas…"

"Who do you want to have pose for you?"

"You two come tomorrow, and I’ll begin by taking some pictures of you in the way I mean."

"Say, what’s in the back of your mind?" Lydia asked, suddenly suspicious. Only now, as the studio was all set up, did she see that everything about it had a sinister, threatening air. "If you think we’re going to come and be your models, you’re dreaming!"

Bice giggled with her, but the next day she came back to Antonino’s apartment, alone.

She was wearing a white linen dress with colored embroidery on the edges of the sleeves and pockets. Her hair was parted and gathered over her temples. She laughed, a bit slyly, bending her head to one side. As he let her in, Antonino studied her manner—a bit coy, a bit ironic—to discover what were the traits that defined her true character.

He made her sit in a big armchair, and stuck his head under the black cloth that came with his camera. It was one of those boxes whose rear wall was of glass, where the image is reflected as if already on the plate, ghostly, a bit milky, deprived of every link with space and time. To Antonino it was as if he had never seen Bice before. She had a docility in her somewhat heavy way of lowering her eyelids, of stretching her neck forward, that promised something hidden, as her smile seemed to hide behind the very act of smiling.

"There. Like that. No, head a bit farther; raise your eyes. No, lower them." Antonino was pursuing, within that box, something of Bice that all at once seemed most precious to him, absolute.

"Now you’re casting a shadow; move into the light. No, it was better before."

There were many possible photographs of Bice and many Bices impossible to photograph, but what he was seeking was the unique photograph that would contain both the former and the latter.

"I can’t get you," his voice emerged, stifled and complaining from beneath the black hood, "I can’t get you any more; I can’t manage to get you."

He freed himself from the cloth and straightened up again. He was going about it all wrong. That expression, that accent, that secret he seemed on the very point of capturing in her face, was something that drew him into the quicksands of moods, humors, psychology: he, too, was one of those who pursue life as it flees, a hunter of the unattainable, like the takers of snapshots.

He had to follow the opposite path: aim at a portrait completely on the surface, evident, unequivocal, that did not elude conventional appearance, the stereotype, the mask. The mask, being first of all a social, historical product, contains more truth than any image claiming to be "true"; it bears a quantity of meanings that will gradually be revealed. Wasn’t this precisely Antonino’s intention in setting up this fair booth of a studio?

He observed Bice. He should start with the exterior elements of her appearance. In Bice’s way of dressing and fixing herself up—he thought—you could recognize the somewhat nostalgic, somewhat ironic intention, widespread in the mode of those years, to hark back to the fashions of thirty years earlier. The photograph should underline this intention: why hadn’t he thought of that?

Antonino went to find a tennis racket; Bice should stand up in a three-quarter turn, the racket under her arm, her face in the pose of a sentimental postcard. To Antonino, from under the black drape, Bice’s image—in its slimness and suitability to the pose, and in the unsuitable and almost incongruous aspects that the pose accentuated—seemed very interesting. He made her change position several times, studying the geometry of legs and arms in relation to the racket and to some element in the background. (In the ideal postcard in his mind there would have been the net of the tennis court, but you couldn’t demand too much, and Antonino made do with a Ping-Pong table.)

But he still didn’t feel on safe ground: wasn’t he perhaps trying to photograph memories—or, rather, vague echoes of recollection surfacing in the memory? Wasn’t his refusal to live the present as a future memory, as the Sunday photographers did, leading him to attempt an equally unreal operation, namely to give a body to recollection, to substitute it for the present before his very eyes?

"Move! Don’t stand there like a stick! Raise the racket, damn it! Pretend you’re playing tennis!" All of a sudden he was furious. He had realized that only by exaggerating the poses could he achieve an objective alienness; only by feigning a movement arrested halfway could he give the impression of the unmoving, the nonliving.

Bice obediently followed his orders even when they became vague and contradictory, with a passivity that was also a way of declaring herself out of the game, and yet somehow insinuating, in this game that was not hers, the unpredictable moves of a mysterious match of her own. What Antonino now was expecting of Bice, telling her to put her legs and arms this way and that way, was not so much the simple performance of a plan as her response to the violence he was doing her with his demands, an unforeseeable aggressive reply to this violence that he was being driven more and more to wreak on her.

It was like a dream, Antonino thought, contemplating, from the darkness in which he was buried, that improbable tennis player filtered into the glass rectangle: like a dream when a presence coming from the depth of memory advances, is recognized, and then suddenly is transformed into something unexpected, something that even before the transformation is already frightening because there’s no telling what it might be transformed into.

Did he want to photograph dreams? This suspicion struck him dumb, hidden in that ostrich refuge of his with the bulb in his hand, like an idiot; and meanwhile Bice, left to herself, continued a kind of grotesque dance, freezing in exaggerated tennis poses, backhand, drive, raising the racket high or lowering it to the ground as if the gaze coming from that glass eye were the ball she continued to slam back.

"Stop, what’s this nonsense? This isn’t what I had in mind." Antonino covered the camera with the cloth and began pacing up and down the room.

It was all the fault of that dress, with its tennis, prewar connotations… It had to be admitted that if she wore a street dress the kind of photograph he described couldn’t be taken. A certain solemnity was needed, a certain pomp, like the official photos of queens. Only in evening dress would Bice become a photographic subject, with the décolleté that marks a distinct line between the white of the skin and the darkness of the fabric, accentuated by the glitter of jewels, a boundary between an essence of woman, almost atemporal and almost impersonal in her nakedness, and the other abstraction, social this time, the dress, symbol of an equally impersonal role, like the drapery of an allegorical statue.

He approached Bice, began to unbutton the dress at the neck and over the bosom, and slip it down over her shoulders. He had thought of certain nineteenth-century photographs of women in which from the white of the cardboard emerge the face, the neck, the line of the bared shoulders, while all the rest disappears into the whiteness.

This was the portrait outside of time and space that he now wanted; he wasn’t quite sure how it was achieved, but he was determined to succeed. He set the spotlight on Bice, moved the camera closer, fiddled around under the cloth adjusting the aperture of the lens. He looked into it. Bice was naked.

She had made the dress slip down to her feet; she wasn’t wearing anything underneath it; she had taken a step forward—no, a step backward, which was as if her whole body were advancing in the picture; she stood erect, tall before the camera, calm, looking straight ahead, as if she were alone.

Antonino felt the sight of her enter his eyes and occupy the whole visual field, removing it from the flux of casual and fragmentary images, concentrating time and space in a finite form. And as if this visual surprise and the impression of the plate were two reflexes connected among themselves, he immediately pressed the bulb, loaded the camera again, snapped, put in another plate, snapped, and went on changing plates and snapping, mumbling, stifled by the cloth, "There, that’s right now, yes, again, I’m getting you fine now, another."

He had run out of plates. He emerged from the cloth. He was pleased. Bice was before him, naked, as if waiting.

"Now you can dress," he said, euphoric, but already in a hurry. "Let’s go out."

She looked at him, bewildered.

"I’ve got you now," he said.

Bice burst into tears.

Antonino realized that he had fallen in love with her that same day. They started living together, and he bought the most modern cameras, telescopic lens, the most advanced equipment; he installed a darkroom. He even had a set-up for photographing her when she was asleep at night. Bice would wake at the flash, annoyed; Antonino went on taking snapshots of her disentangling herself from sleep, of her becoming furious with him, of her trying in vain to find sleep again by plunging her face into the pillow, of her making up with him, of her recognizing as acts of love these photographic rapes.

In Antonino’s darkroom, strung with films and proofs, Bice peered from every frame, as thousands of bees peer out from the honeycomb of a hive, but always the same bee: Bice in every attitude, at every angle, in every guise, Bice posed or caught unaware, an identity fragmented into a powder of images.

"But what’s this obsession with Bice? Can’t you photograph anything else?" was the question he heard constantly from his friends, and also from her.

"It isn’t just a matter of Bice," he answered. "It’s a question of method. Whatever person you decide to photograph, or whatever thing, you must go on photographing it always, exclusively, at every hour of the day and night. Photography has a meaning only if it exhausts all possible images."

But he didn’t say what meant most to him: to catch Bice in the street when she didn’t know he was watching her, to keep her in the range of hidden lenses, to photograph her not only without letting himself be seen but without seeing her, to surprise her as she was in the absence of his gaze, of any gaze. Not that he wanted to discover any particular thing; he wasn’t a jealous man in the usual sense of the word. It was an invisible Bice that he wanted to possess, a Bice absolutely alone, a Bice whose presence presupposed the absence of him and everyone else.

Whether or not it could be defined as jealousy, it was, in any case, a passion difficult to put up with. And soon Bice left him.

Antonino sank into deep depression. He began to keep a diary—a photographic diary, of course. With the camera slung around his neck, shut up in the house, slumped in an armchair, he compulsively snapped pictures as he stared into the void. He was photographing the absence of Bice.

He collected the photographs in an album: you could see ashtrays brimming with cigarette butts, an unmade bed, a damp stain on the wall. He got the idea of composing a catalogue of everything in the world that resists photography, that is systematically omitted from the visual field not only by camera but also by human beings. On every subject he spent days, using up whole rolls at intervals of hours, so as to follow the changes of light and shadow. One day he became obsessed with a completely empty corner of the room, containing a radiator pipe and nothing else: he was tempted to go on photographing that spot and only that till the end of his days.

The apartment was completely neglected; old newspapers, letters lay crumpled on the floor, and he photographed them. The photographs in the papers were photographed as well, and an indirect bond was established between his lens and that of distant news photographers. To produce those black spots the lenses of other cameras had been aimed at police assaults, charred automobiles, running athletes, ministers, defendants.

Antonino now felt a special pleasure in portraying domestic objects framed by a mosaic of telephotos, violent patches of ink on white sheets. From his immobility he was surprised to find he envied the life of the news photographer, who moves following the movements of crowds, bloodshed, tears, feasts, crime, the conventions of fashion, the falsity of official ceremonies; the news photographer, who documents the extremes of society, the richest and the poorest, the exceptional moments that are nevertheless produced at every moment and in every place.

Does this mean that only the exceptional condition has a meaning? Antonino asked himself. Is the news photographer the true antagonist of the Sunday photographer? Are their worlds mutually exclusive? Or does the one give meaning to the other?

Reflecting like this, he began to tear up the photographs with Bice or without Bice that had accumulated during the months of his passion, ripping to pieces the strips of proofs hung on the walls, snipping up the celluloid of the negatives, jabbing the slides, and piling the remains of this methodical destruction on newspapers spread out on the floor.

Perhaps true, total photography, he thought, is a pile of fragments of private images, against the creased background of massacres and coronations.

He folded the corners of the newspapers into a huge bundle to be thrown into the trash, but first he wanted to photograph it. He arranged the edges so that you could clearly see two halves of photographs from different newspapers that in the bundle happened, by chance, to fit together. In fact he reopened the package a little so that a bit of shiny pasteboard would stick out, the fragment of a torn enlargement. He turned on a spotlight; he wanted it to be possible to recognize in his photograph the half-crumpled and torn images, and at the same time to feel their unreality as casual, inky shadows, and also at the same time their concreteness as objects charged with meaning, the strength with which they clung to the attention that tried to drive them away.

To get all this into one photograph he had to acquire an extraordinary technical skill, but only then would Antonino quit taking pictures. Having exhausted every possibility, at the moment when he was coming full circle Antonino realized that photographing photographs was the only course that he had left—or, rather, the true course he had obscurely been seeking all this time.

2010/2/11

RIP: Eric Rohmer (1920~2010) 侯麥,再見

The Grave of Eric Rohmer (Maurice Scherer), Montparnasse Cemetery, Paris.

這天就像電影《冬天的故事》的溫度色調

大雪裡帶著一點溫暖的紅

不斷低頭、尋尋覓覓

終於找到侯麥不久前剛下葬的墓地

在大名鼎鼎、文人冠蓋雲集的Montparnasse墓園裡

侯麥的墓,一如其電影般

避免浮誇、簡約低調、謙遜自在

摒除一切不必要的宗教符號與凡塵圖騰

靜靜的退避在墓園一個極不顯眼處

上面只簡單列出他的本名Maurice Scherer與生卒年

好似看盡俗世的虛榮浮華

而寧可選擇一個拒絕討好、無須喧囂、匿名隱身,卻怡然自在的位置

或許他知道,時間的課題,正是人生最大的道德寓言。

侯麥,再見。

Eric Rohmer obituary

Idiosyncratic French film-maker who was a leading figure in the cinema of the postwar new wave

- Tom Milne

- guardian.co.uk, Monday 11 January 2010 20.09 GMT

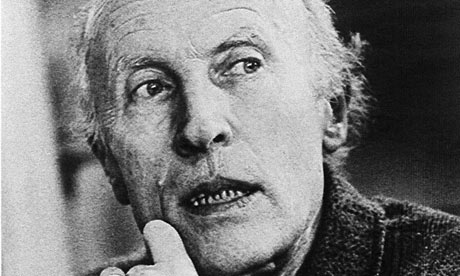

Eric Rohmer in 1985. Photograph: EPA

Behind that exchange lies a jab at Hollywood's mistrust of any film-maker, especially a French one, who neglects plot and action in favour of cerebral exploration, metaphysical conceit and moral nuance. The Dream Factory, after all, had proved through trial and error that cinema is cinema, literature is literature, and the twain shall meet only provided the images rule, not the words.

Of the major American film-makers, perhaps only Joseph Mankiewicz allowed his scripts, fuelled by his own sparkling dialogue, to wag the tail of his movies. While acknowledging the brilliance, Hollywood punditry never failed to complain that Mankiewicz characters simply talked too much.

Rohmer, who has died aged 89, pushed even further into this disputed territory. The oldest of the group of critics associated with the film review Cahiers du Cinéma, who launched the French new wave in the late 1950s, Rohmer had (writing initially under his real name of Maurice Schérer) established impeccable credentials for a future film-maker. Among the objects of his admiration were Dashiell Hammett, Alfred Hitchcock (about whom he wrote a monograph with Claude Chabrol), Howard Hawks, and above all FW Murnau, the great visual stylist of the German expressionist era (on whose version of Faust he published a doctoral thesis). As a film-maker, however, he turned instead to such literary-philosophical luminaries as Blaise Pascal, Denis Diderot, Choderlos de Laclos and Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

His first feature, Le Signe du Lion (The Sign of Leo), completed in 1959 after one false start and a handful of shorts, fitted comfortably into the early new wave formula of Parisian life, with its tale of a student musician, tempted into debt by a promised inheritance, who lapses into abject destitution after the legacy turns out to be a hoax. In retrospect, one can clearly see in it the seeds of Rohmer's later work. Showing little interest in plot or action, Rohmer concentrates on demonstrating how Paris itself becomes an objective correlative to the hero's state of mind, gradually metamorphosing from a welcoming city into a bleak stone desert as he realises that the friends from whom he might hope to borrow are all away for the vacation.

With Le Signe du Lion failing at the box office, Rohmer retreated into television where, while working on educational documentaries, he hatched his daring conception for a series of Six Moral Tales. Variations on a theme, each film would deal with "a man meeting a woman at the very moment when he is about to commit himself to someone else". Furthermore, as Rohmer later observed, the films would deal "less with what people do than with what is going on in their minds while they are doing it".

Made for TV, the first two films in the cycle, La Boulangère de Monceau (The Baker of Monceau, 1962) and La Carrière de Susanne (Suzanne's Career, 1963), shot in black and white and running for 26 and 60 minutes respectively, were too cramped in every respect to be more than clumsy foretastes of what was to come.

Completing the series for the cinema with La Collectionneuse (The Collector, 1966), Ma Nuit Chez Maud (My Night With Maud, 1969), his international breakthrough Le Genou de Claire (Claire's Knee, 1970) and L'Amour l'Après-midi (Love in the Afternoon, 1972), Rohmer found exactly what he needed in the bigger screens, longer running times, more expansive locations and availability of colour (actually in black and white, My Night With Maud uses the snowy landscapes of Clermont-Ferrand as a perfect counterpoint to its chilly Pascalian thematic). Backed by the richly sensuous role now played by the visuals, the somewhat arid intellectual dandyism of the first two films flowered into a teasingly metaphysical exploration of human foibles.

Le Genou de Claire, for instance, perhaps the most accomplished of the six films, is about a French diplomat, on the brink of both middle age and marriage, enjoying a brief lakeside vacation at Lake Annecy in France. Seduced by his idyllic summery surroundings, he begins casting an appreciative eye over the young women on show. Innocent dalliance, he assures himself, proclaiming that his courtly fancy has been captured by the perfection of the eponymous heroine's knee. Deeper down, though, as he comes to realise when a pert and pretty teenager responds to his casual flirtation by remarking on his resemblance to her father, lies a less palatable truth: there, but for the grace of God, goes a dirty old man.

Rohmer followed his Six Moral Tales with two similar cycles, identical in style, method and accomplishment. First came Comedies and Proverbs: La Femme de l'Aviateur (The Aviator's Wife, 1980), Le Beau Mariage (A Good Marriage, 1981), Pauline à la Plage (Pauline at the Beach, 1982), Les Nuits de la Pleine Lune (Full Moon in Paris, 1984), Le Rayon Vert (The Green Ray, 1986) and L'Ami de Mon Amie (My Girlfriend's Boyfriend, 1987). Then, Tales of the Four Seasons: Conte de Printemps (A Tale of Springtime, 1989), Conte d'Hiver (A Winter's Tale, 1992), Conte d'Eté (A Summer's Tale, 1996) and Conte d'Automne (An Autumn Tale, 1998).

In between times, Rohmer also made a number of non-series films, most notably two literary adaptations which are rather different in their visual approach. Die Marquise von O... (The Marquise of O, 1976) adopts a severe neo-classical style in transposing Heinrich von Kleist's teasing early-19th-century novella about the social furore occasioned when a chaste young widow suffers a pregnancy which she insists can only be the result of an immaculate conception. Perceval le Gallois (1978), on the other hand, toys joyously with cut-out sets and false perspectives to invest his adaptation of Chrétien de Troyes's 12th-century Arthurian tale with the faux-naif aspects of an illuminated manuscript.

Both remain entirely consistent with the body of Rohmer's work, a highly original and endlessly fascinating attempt to render the interior exterior by mapping out the maze of misdirections that bedevil communications between the human heart and mind.

Rohmer guarded his private life fiercely – giving different versions of his date of birth and real name on different occasions, so that it is difficult to be certain of the truth. He was married in 1957 to Thérèse Barbet, and they had two sons.

Ronald Bergan writes: The Lady and the Duke (L'Anglaise et le Duc, 2001), set during the French Revolution, is as elegant as the heroine, a patrician Englishwoman who defies the citizens' committees. Always experimenting with visual style to suit the subject, Rohmer had the actors seen against artificial tableaux of Paris circa 1792. However, these are not painted backdrops, but perspective drawings, which are intriguingly combined with the action through digital means. It proved that Rohmer at 81 was willing to utilise new technology.