The Grave of Eric Rohmer (Maurice Scherer), Montparnasse Cemetery, Paris.

這天就像電影《冬天的故事》的溫度色調

大雪裡帶著一點溫暖的紅

不斷低頭、尋尋覓覓

終於找到侯麥不久前剛下葬的墓地

在大名鼎鼎、文人冠蓋雲集的Montparnasse墓園裡

侯麥的墓,一如其電影般

避免浮誇、簡約低調、謙遜自在

摒除一切不必要的宗教符號與凡塵圖騰

靜靜的退避在墓園一個極不顯眼處

上面只簡單列出他的本名Maurice Scherer與生卒年

好似看盡俗世的虛榮浮華

而寧可選擇一個拒絕討好、無須喧囂、匿名隱身,卻怡然自在的位置

或許他知道,時間的課題,正是人生最大的道德寓言。

侯麥,再見。

Eric Rohmer obituary

Idiosyncratic French film-maker who was a leading figure in the cinema of the postwar new wave

- guardian.co.uk, Monday 11 January 2010 20.09 GMT

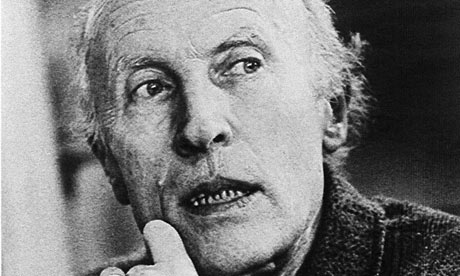

Eric Rohmer in 1985. Photograph: EPA

Behind that exchange lies a jab at Hollywood's mistrust of any film-maker, especially a French one, who neglects plot and action in favour of cerebral exploration, metaphysical conceit and moral nuance. The Dream Factory, after all, had proved through trial and error that cinema is cinema, literature is literature, and the twain shall meet only provided the images rule, not the words.

Of the major American film-makers, perhaps only Joseph Mankiewicz allowed his scripts, fuelled by his own sparkling dialogue, to wag the tail of his movies. While acknowledging the brilliance, Hollywood punditry never failed to complain that Mankiewicz characters simply talked too much.

Rohmer, who has died aged 89, pushed even further into this disputed territory. The oldest of the group of critics associated with the film review Cahiers du Cinéma, who launched the French new wave in the late 1950s, Rohmer had (writing initially under his real name of Maurice Schérer) established impeccable credentials for a future film-maker. Among the objects of his admiration were Dashiell Hammett, Alfred Hitchcock (about whom he wrote a monograph with Claude Chabrol), Howard Hawks, and above all FW Murnau, the great visual stylist of the German expressionist era (on whose version of Faust he published a doctoral thesis). As a film-maker, however, he turned instead to such literary-philosophical luminaries as Blaise Pascal, Denis Diderot, Choderlos de Laclos and Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

His first feature, Le Signe du Lion (The Sign of Leo), completed in 1959 after one false start and a handful of shorts, fitted comfortably into the early new wave formula of Parisian life, with its tale of a student musician, tempted into debt by a promised inheritance, who lapses into abject destitution after the legacy turns out to be a hoax. In retrospect, one can clearly see in it the seeds of Rohmer's later work. Showing little interest in plot or action, Rohmer concentrates on demonstrating how Paris itself becomes an objective correlative to the hero's state of mind, gradually metamorphosing from a welcoming city into a bleak stone desert as he realises that the friends from whom he might hope to borrow are all away for the vacation.

With Le Signe du Lion failing at the box office, Rohmer retreated into television where, while working on educational documentaries, he hatched his daring conception for a series of Six Moral Tales. Variations on a theme, each film would deal with "a man meeting a woman at the very moment when he is about to commit himself to someone else". Furthermore, as Rohmer later observed, the films would deal "less with what people do than with what is going on in their minds while they are doing it".

Made for TV, the first two films in the cycle, La Boulangère de Monceau (The Baker of Monceau, 1962) and La Carrière de Susanne (Suzanne's Career, 1963), shot in black and white and running for 26 and 60 minutes respectively, were too cramped in every respect to be more than clumsy foretastes of what was to come.

Completing the series for the cinema with La Collectionneuse (The Collector, 1966), Ma Nuit Chez Maud (My Night With Maud, 1969), his international breakthrough Le Genou de Claire (Claire's Knee, 1970) and L'Amour l'Après-midi (Love in the Afternoon, 1972), Rohmer found exactly what he needed in the bigger screens, longer running times, more expansive locations and availability of colour (actually in black and white, My Night With Maud uses the snowy landscapes of Clermont-Ferrand as a perfect counterpoint to its chilly Pascalian thematic). Backed by the richly sensuous role now played by the visuals, the somewhat arid intellectual dandyism of the first two films flowered into a teasingly metaphysical exploration of human foibles.

Le Genou de Claire, for instance, perhaps the most accomplished of the six films, is about a French diplomat, on the brink of both middle age and marriage, enjoying a brief lakeside vacation at Lake Annecy in France. Seduced by his idyllic summery surroundings, he begins casting an appreciative eye over the young women on show. Innocent dalliance, he assures himself, proclaiming that his courtly fancy has been captured by the perfection of the eponymous heroine's knee. Deeper down, though, as he comes to realise when a pert and pretty teenager responds to his casual flirtation by remarking on his resemblance to her father, lies a less palatable truth: there, but for the grace of God, goes a dirty old man.

Rohmer followed his Six Moral Tales with two similar cycles, identical in style, method and accomplishment. First came Comedies and Proverbs: La Femme de l'Aviateur (The Aviator's Wife, 1980), Le Beau Mariage (A Good Marriage, 1981), Pauline à la Plage (Pauline at the Beach, 1982), Les Nuits de la Pleine Lune (Full Moon in Paris, 1984), Le Rayon Vert (The Green Ray, 1986) and L'Ami de Mon Amie (My Girlfriend's Boyfriend, 1987). Then, Tales of the Four Seasons: Conte de Printemps (A Tale of Springtime, 1989), Conte d'Hiver (A Winter's Tale, 1992), Conte d'Eté (A Summer's Tale, 1996) and Conte d'Automne (An Autumn Tale, 1998).

In between times, Rohmer also made a number of non-series films, most notably two literary adaptations which are rather different in their visual approach. Die Marquise von O... (The Marquise of O, 1976) adopts a severe neo-classical style in transposing Heinrich von Kleist's teasing early-19th-century novella about the social furore occasioned when a chaste young widow suffers a pregnancy which she insists can only be the result of an immaculate conception. Perceval le Gallois (1978), on the other hand, toys joyously with cut-out sets and false perspectives to invest his adaptation of Chrétien de Troyes's 12th-century Arthurian tale with the faux-naif aspects of an illuminated manuscript.

Both remain entirely consistent with the body of Rohmer's work, a highly original and endlessly fascinating attempt to render the interior exterior by mapping out the maze of misdirections that bedevil communications between the human heart and mind.

Rohmer guarded his private life fiercely – giving different versions of his date of birth and real name on different occasions, so that it is difficult to be certain of the truth. He was married in 1957 to Thérèse Barbet, and they had two sons.

Ronald Bergan writes: The Lady and the Duke (L'Anglaise et le Duc, 2001), set during the French Revolution, is as elegant as the heroine, a patrician Englishwoman who defies the citizens' committees. Always experimenting with visual style to suit the subject, Rohmer had the actors seen against artificial tableaux of Paris circa 1792. However, these are not painted backdrops, but perspective drawings, which are intriguingly combined with the action through digital means. It proved that Rohmer at 81 was willing to utilise new technology.

His last film, The Romance of Astrea and Celadon (Les Amours d'Astrée et de Céladon, 2007) revealed him as interested in the combination of the intellectual with the sensual among young people. Rohmer's achievement lies in recreating fifth-century Gaul, with shepherds, shepherdesses, druids and nymphs, and making it meaningful to a modern audience. If Rohmer's contemporary films evoked 18th-century novels and plays, his period pieces echoed present-day sexual relationships. Rohmer's characters are largely defined by their relationships with the opposite sex, which take place in sumptuous hedonistic settings. For films that deal to a large extent with resisting temptation, they are tantalisingly erotic.

• Eric Rohmer (Maurice Henri Joseph Schérer), film director, born 21 March 1920; died 11 January 2010

• Tom Milne died in 2005

沒有留言:

張貼留言